- Breakthrough For Ehlers Danlos Syndrome and Endometriosis - 13 March 2025

- Does EDS get worse as you age? - 20 February 2025

- Can Ehlers Danlos Syndrome Cause Weight Gain/Loss? - 18 February 2025

If you’ve ever felt like your body is working against you when it comes to Ehlers Danlos syndrome and weight gain, then you’re not alone. I’ve worked with countless people with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) in a rehab capacity, and it’s astonishing how many noticed their weight creeping up, or simply struggled to stay stable, despite eating well and doing what they can to move. And on the other hand, many who have struggled to gain weight.

And yet, when they bring it up with their doctor, many are met with the age old “Just eat less and exercise more”, or probably more commonly the “EDS doesn’t cause weight gain” favourite. Most disappointingly, for those with gastric issues, wherein eating food is a daily struggle, it’s not uncommon for them to go many, many, years without help from the system.

It’s frustrating because while EDS itself does not directly cause weight gain: it absolutely does influence the many, many, factors that do, such as reduced mobility, chronic pain. Likewise, the very nature of EDS and how it affects collagen, in particular the gastrointestinal track, can for many, cause lots of issue with staying at a healthy weight.

Weight gain or indeed weight loss, is a complex subject when Ehlers Danlos syndrome is thrown into the mix, weight regulation in EDS is far more complicated than “Just eat more/less.”

So, in this article, we’re going to look at it properly, but if you’re also looking for an incredibly extensive resource on EDS and diet in general, definitely check out our mammoth article on Diet and hypermobility/EDS.

This article covers:

ToggleDecondition in Ehlers Danlos syndrome and Hypermobility

For most people, exercise is simple: move more, burn more, lose weight, BLAH BLAH BLAH. But when you have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), movement isn’t just tiring, it can also be dangerous. When your joints can sublux from walking, your muscles can fatigue after five minutes, and your heart rate can skyrocket just from standing up, how exactly are you supposed to “just move more”?

The answer? You can’t, at least, not in the way most people think.

And that’s where the problem starts. Most people move through life without thinking much about their joints. Their knees don’t suddenly pop out when stepping off a curb, their shoulders don’t sublux from reaching for a coffee mug, and they don’t have to plan their entire day around whether their body will cooperate. But in EDS, every movement can carry a level of risk depending on how lax you are. One study actually found that 50% of people with EDS avoid exercise due to fear of injury, and a massive 87% experience pain during physical activity. That’s not just about being “out of shape” it’s about survival. Because if every time you try to move, your body punishes you for it, why wouldn’t your activity levels dip.

The Deconditioning Cycle

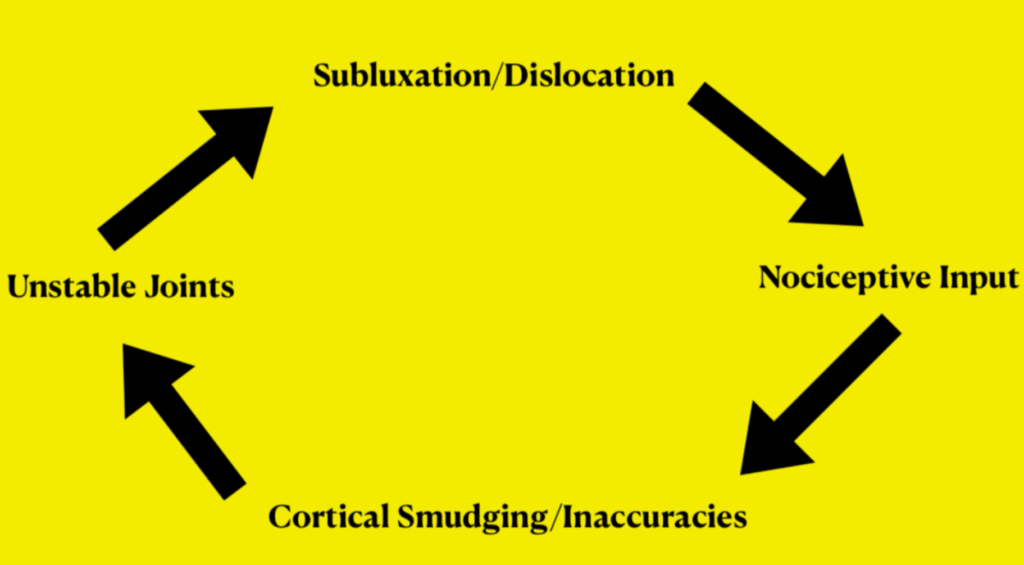

When a joint subluxes or dislocates, the body’s nociceptive system, its built-in alarm system fires up, sending urgent messages to the brain about potential danger/damage. This makes perfect sense in the short term; the body is trying to protect itself from actual or potential damage. On the surface, this might seem helpful, as if a movement causes injury, surely avoiding that movement is the safest option.

But here’s the problem: avoiding movement means that it’s not just the muscles surrounding the joint weaken over time, but the actual motor system. Weaker muscles mean less support for the joint, less support makes another subluxation more likely, which then triggers another pain response and more guarding from the nervous system. The next time the person moves, the joint is even more unstable, making subluxation or dislocation even more likely. Over time, the brain starts to perceive movement itself as a threat, and the cycle repeats.

Each subluxation, each injury, and each moment of guarding sends more blurry, nociceptive-driven information to the brain, making it harder for the brain to accurately process where the joint is in space. As a result, the body’s ability to stabilize itself gets worse, not better.

At this point, movement feels impossible, and the person withdraws even further from physical activity. Weight gain follows, not because of poor lifestyle choices, but because the body is trapped in a pattern of instability, fear, and avoidance.

Hypermobile Exercise and Cortical Maps

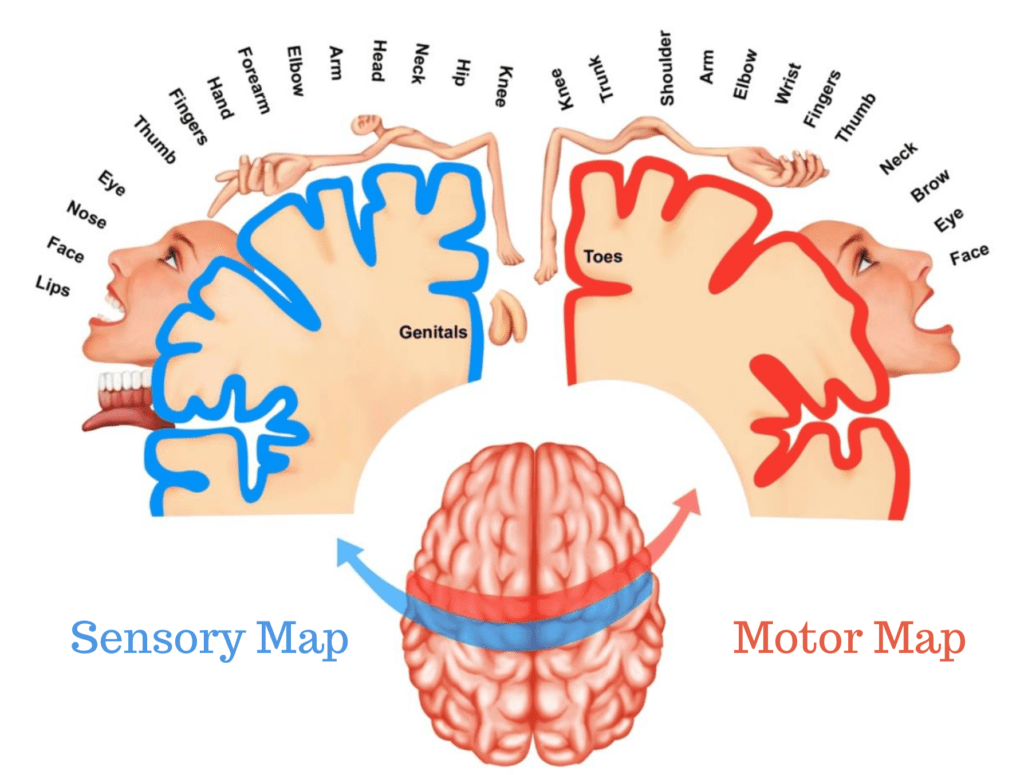

Most people assume that stabilizing hypermobile joints is all about building muscle. But hypermobility isn’t just a structural problem: it’s a neurological one. In a healthy body, the brain has a detailed map of the body stored in the somatosensory cortex.

This map helps track where each joint is in space, allowing for smooth, controlled movement. But in hypermobility, this map often becomes distorted or blurry from repeated subluxations/dislocations, and injuries.

Every time a joint subluxes, dislocates, or sends prolonged danger signals, the brain’s ability to accurately map that joint deteriorates. If the brain doesn’t know where a joint is, it can’t stabilize it properly. This is why movement in hypermobility often feels uncoordinated, unpredictable, or even unsafe. Imagine driving with a GPS that keeps losing signal and recalculating. You second-guess every turn, slow down, and make unnecessary corrections.

That’s exactly what happens when the brain isn’t confident about where a joint is, movement becomes inefficient, joints feel unstable, and the risk of injury increases.

This is why the standard “just build muscle” approach often fails people with hypermobility. If the brain’s map of the body is inaccurate, then it doesn’t matter how strong the muscles are, the nervous system won’t use them effectively.

This explains why some people with significant muscle mass still experience instability, while others with less muscle seem to function better. The difference isn’t just strength, it’s how well the brain can map and control the joints.

Many people with EDS fall into a boom-and-bust cycle with exercise. They push through discomfort, feel like they’re making progress, and then suddenly experience a EDS flare-up or injury.

Over the years, working with clients, we haven’t just focused on strengthening muscles, we focus on remapping the brain’s understanding of movement. Because, if the brain has a poor map of the body, it will struggle to stabilize joints, no matter how much strength someone builds. Instead of throwing more strength at the problem, we teach the nervous system how to interpret sensory information correctly.

We start with sensory input training, helping the brain rebuild an accurate picture of where the joints are in space. Once this is done, we work on motor control and progressive load, but only when the body is ready for it. This ensures that when strength training is introduced, the muscles can actually do their job effectively. If you want to learn more about cortical mapping you can check out our Hypermoblity and Exercise article here.

This is why many of our clients, most who have struggled for years with traditional rehab, start seeing progress in ways they never have before. It’s not about forcing the body to move, it’s about making movement feel safe, stable, and predictable again. You can see some of our client’s stories here.

Gastrointestinal (GI) Dysfunction and Weight Changes in EDS

If you’ve got Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), chances are your gut isn’t exactly your best friend. Digestive issues are incredibly common, particularly in those with hypermobile EDS (hEDS), with most research showing that up to a staggering 86% of people with hEDS experience some form of GI dysfunction.

That’s not just a coincidence: it’s a pattern that plays a major role in weight regulation.

For some, this means bloating, nausea, and unpredictable digestion. For others, it’s painful reflux, constipation, diarrhea, or gastroparesis (delayed stomach emptying). And when your gut isn’t working properly, unfortunately, your relationship with food, your metabolism, and indeed your ability to absorb nutrients, all take a hit.

It’s not just occasional stomach aches—we’re talking about chronic, persistent gut dysfunction. Studies show that functional GI disorders, like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), affect 37% of people with hEDS. Meanwhile, gastroparesis, where the stomach takes its sweet time emptying food, is common enough that it’s become a hallmark issue in many EDS patients. And it’s not just the stomach that struggles. Dysmotility (abnormal movement) has been found in 76.2% of EDS patients, affecting the entire GI tract from the oesophagus to the colon. That means food isn’t moving through as it should: leading to sluggish digestion, constipation, reflux, and bloating.

So, what does that have to do with weight? A lot.

Malabsorption, Altered Hunger Signals, and Gut Microbiome Imbalances

The gut isn’t just a food processor, it’s the control centre for nutrient absorption, metabolism, and even hunger regulation. When digestion slows down or becomes erratic (as it does with dysmotility and gastroparesis), it disrupts the body’s ability to absorb nutrients properly.

This leads to two major problems:

- Malabsorption: Essential nutrients don’t get absorbed properly, leading to deficiencies and unpredictable energy levels.

- Gut Microbiome Imbalances: Research shows that imbalanced gut bacteria can influence both weight gain and weight loss by altering how the body processes and stores calories.

On top of that, delayed gastric emptying confuses hunger signals. When food sits in the stomach for too long, you might feel full too quickly and struggle to eat enough, leading to unintentional weight loss. But at other times, you might experience sudden hunger spikes when digestion finally catches up, which can trigger cravings for quick, high-calorie foods.

If you’ve ever experienced bloating that made you feel six months pregnant, you know how quickly it can shut down your appetite. Gastroparesis and dysmotility often cause extreme bloating, nausea, and pain, making it hard to eat, hard to digest, and hard to predict how your body will react to food.

For many people with EDS, this leads to dietary restriction, not by choice, but by necessity. You might find yourself avoiding fibber, skipping meals, or relying on “safe” foods that don’t upset your stomach (which, unfortunately, are often nutrient-poor but calorie-dense).

Over time, this can cause:

- Nutritional deficiencies (which slow down metabolism and contribute to fatigue).

- Weight loss due to inadequate intake.

- Weight gain from reliance on high-calorie, low-nutrient foods that are easier to digest.

And because every case of EDS is different, some people with GI issues experience unintentional weight gain, while others struggle to maintain their weight. Either way, it’s not as simple as “eating less or moving more” instead it’s your gut calling the shots.

Mast Cell Activation Syndrome and Weight Changes

For many people with EDS, food isn’t just fuel, it’s a huge daily trigger. One day, a meal sits fine, and the next, well it leads to bloating, cramping, or nausea, for no real clear reason. This unpredictability often traces back to Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS), a condition where mast cells (immune cells abundant in the gut) release excessive histamine and inflammatory chemicals, triggering gut hypersensitivity, food reactions, and metabolic chaos.

When mast cells misfire in the digestive system, they disrupt motility, gut barrier function, and nutrient absorption. This can lead to diarrhoea, constipation, and even “leaky gut,” where unwanted particles enter the bloodstream, worsening inflammation.

Over time, chronic gut inflammation can slow the metabolism, increases insulin resistance, and alters fat storage: explaining why some people with MCAS struggle with weight gain while others lose weight due to malabsorption and food avoidance.

Histamine Intolerance and Food Restrictions

MCAS often presents as histamine intolerance, where high-histamine foods like aged cheeses, alcohol, and fermented products trigger digestive distress. Since histamine affects gut motility and smooth muscle contraction, many people experience pain, bloating, or reflux after eating even small amounts.

To manage symptoms, many resort to restrictive diets, eliminating entire food groups. While this can bring relief, it also leads to nutritional deficiencies, unstable energy levels, and metabolic disruptions, further complicating weight regulation. Some people find themselves losing weight unintentionally, while others gain due to relying on calorie-dense, low-nutrient foods that feel “safe.”

MCAS, Inflammation, and Metabolism

Beyond digestion, MCAS-induced inflammation disrupts metabolism at a deeper level. Chronic mast cell activation has been linked to insulin resistance, increased cortisol, and disrupted appetite regulation, making it harder for the body to burn fat efficiently or maintain stable blood sugar. This explains why many people with MCAS experience unexplained weight gain or fluctuating energy levels, despite eating carefully.

MCAS doesn’t just make eating difficult, it fundamentally alters how the body processes nutrients, burns energy, and regulates weight. Managing it isn’t just about cutting out histamine, it’s about reducing inflammation, stabilizing gut function, and ensuring proper nutrient absorption. Until the medical world stops dismissing these symptoms as “just IBS” or “just sensitivities,” people with EDS will continue to be left without answers.

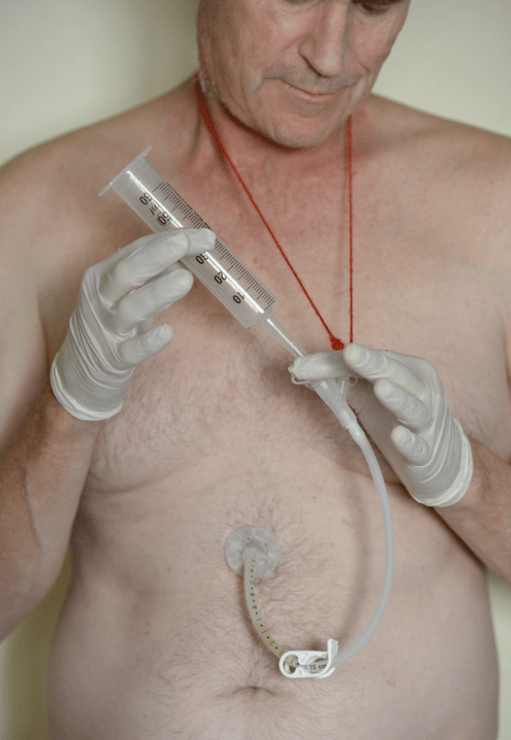

Feeding Tubes for Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Eating should be simple, you feel hunger, you eat, and your body absorbs the nutrients it needs to function. But for many with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), this basic process becomes a battleground. Like we ran through earlier, issues like Gastroparesis slow down the stomach’s ability to empty food, and Dysphagia makes swallowing incredibly difficult. Chronic nausea and vomiting turn meals into a cycle of discomfort and malnutrition. Over time, even the best dietary adjustments, medications, and lifestyle changes fail to keep up with the body’s needs. When that happens, feeding tubes become the next line of defense.

Unlike Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) (something we will talk about later), which bypasses digestion entirely by delivering nutrients directly into the bloodstream, feeding tubes still use the digestive system, just in a way that circumvents the parts that aren’t functioning properly. This is crucial, because when the gut isn’t used, it deteriorates, increasing the risk of infections, bacterial overgrowth, and a cascade of other complications.

Why Feeding Tubes Are Used in EDS

EDS comes with a unique set of challenges when it comes to digestion. Connective tissue abnormalities mean that the gut itself is structurally weaker, leading to poor motility, digestive dysfunction, and problems with absorption. Autonomic dysfunction, commonly seen in hypermobile EDS (hEDS), adds another layer of complexity, affecting the way the nervous system regulates digestion. It’s not just about an uncooperative stomach; the entire gastrointestinal tract, from swallowing to bowel movements, can allbe affected.

For some, this means they can still eat but struggle to consume enough calories to maintain their weight. For others, eating becomes a full-time job, one filled with pain, bloating, and exhaustion that ultimately leads to dangerous weight loss and malnutrition. When this happens, feeding tubes become essential.

The decision to place a feeding tube is never taken lightly. It typically comes after a long and exhausting period of declining health, failed dietary interventions, and increasing medical interventions to manage malnutrition. By the time most EDS patients are offered a feeding tube, they’ve already tried everything else.

Types of Feeding Tubes and How They Work

The type of tube used depends on the severity of the dysfunction and how much of the gastrointestinal tract is still functioning. For some, the stomach is still usable, just not through oral intake. For others, the stomach is a lost cause, and nutrition needs to go straight to the small intestine.

Short-term options like nasojejunal (NJ) tubes are often used first. These tubes are inserted through the nose and travel down into the small intestine, bypassing the stomach entirely. NJ tubes are commonly used as a trial to see if a more permanent solution is needed. They’re effective but not ideal for long-term use, as they can be uncomfortable, easy to dislodge, and socially challenging due to their visibility.

For those who need long-term support, surgically placed feeding tubes are the next step. A G-tube (gastrostomy tube)is placed directly into the stomach through the abdominal wall. It’s a good option for those who can still tolerate stomach feeding but cannot eat normally. However, if severe gastroparesis, reflux, or nausea make stomach feeding impossible, a J-tube (jejunostomy tube) may be required. This bypasses the stomach entirely, delivering nutrition straight to the small intestine. Some patients use a GJ-tube (gastrojejunostomy tube), which allows feeding into either the stomach or the intestine depending on tolerance.

The Benefits of Enteral Nutrition in EDS

For those with EDS-related GI dysfunction, feeding tubes can be life-changing. They provide consistent nutrition, hydration, and caloric intake that would otherwise be impossible. Research has shown that patients with chronic malnutrition due to digestive disorders see improvements in energy levels, symptom control, and weight stabilization after initiating enteral feeding. When food intake is no longer a source of stress and suffering, many patients regain strength and improve their overall quality of life.

By bypassing the parts of the GI tract that are dysfunctional, feeding tubes reduce symptoms like nausea, vomiting, bloating, and pain. For those with gastroparesis, jejunal feeding is particularly effective, as it prevents food from lingering in the stomach and causing delays in digestion.

But the biggest advantage of enteral nutrition over TPN is that it keeps the gut active. The digestive system isn’t just there to process food—it plays a huge role in immune function. When the gut isn’t used, the risk of infections increases, gut bacteria become imbalanced, and overall health starts to decline. Feeding tubes allow the body to continue using its digestive system as much as possible, which is crucial for long-term health.

The Challenges of Feeding Tubes in EDS

Despite their benefits, feeding tubes are not without complications—especially for those with EDS. Fragile connective tissue makes surgical placement more complex and increases the risk of complications like slow healing, infections, and tube dislodgement. For patients with severe autonomic dysfunction, enteral feeding can also lead to difficulties with hydration and electrolyte balance.

One of the most common challenges with feeding tubes is formula intolerance. Standard enteral formulas don’t always work for EDS patients, especially those with mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Many experience severe bloating, pain, and diarrhea with certain formulas, requiring careful adjustments to find one that is well-tolerated.

Social stigma is another issue, especially for those using nasal tubes. While G-tubes and J-tubes are more discreet, nasojejunal tubes are highly visible and can lead to unwanted attention, questions, and even bullying in younger patients. This can add an emotional toll on top of the already exhausting reality of living with a chronic illness.

For those who require long-term enteral feeding, there’s also the psychological challenge of accepting the loss of a basic function. Eating is more than just fueling the body, it’s social, cultural, and emotional. Having to rely on a tube for nutrition can feel isolating and frustrating, even when it’s the best possible solution for sustaining health.

Exploring Alternatives Before Feeding Tubes

Given the challenges of enteral nutrition, feeding tubes are generally considered after all other options have been explored. Some patients are able to avoid tube placement with aggressive dietary management, motility enhancing medications, and autonomic rehabilitation.

Prokinetic drugs like prucalopride or erythromycin can improve gastric motility, making it easier to tolerate oral intake. Some find that neuromodulatory treatments, like vagus nerve stimulation, help regulate autonomic dysfunction and improve digestion. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has even been shown to help some patients overcome food aversions and anxiety around eating.

That said, when weight loss becomes severe or malnutrition starts affecting organ function, feeding tubes become the safest and most effective way to sustain the body.

Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN)

Sometimes feeding tubes just dont work, and for those whose GI systems have essentially shut down, Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) becomes a last resort. TPN is an intravenous feeding method that bypasses the digestive system entirely, delivering nutrients directly into the bloodstream. It can be life-saving for individuals with severe intestinal failure, short bowel syndrome, or chronic intestinal dysmotility, all of which are seen in EDS patients.

However, TPN is not without risks, and over the years we have worked with many clients where TPN has caused some major issues. Studies show that patients on long-term TPN face a high risk of infections due to the need for a central venous catheter. The risk of central line associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) is particularly concerning, with some studies actually reporting infection rates as high as 18.8 per 1,000 catheter days. Since EDS already affects connective tissue and healing, infections can quickly become life-threatening.

Going beyond infections, metabolic complications such as hyperglycemia, electrolyte imbalances, and refeeding syndromeare well-documented risks. In fact, up to 72% of long-term TPN users develop liver dysfunction, which can eventually progress to parenteral nutrition-associated cholestasis (PNAC) and liver failure.

For many of our clients we have seen, the decision to start TPN wasn’t taken lightly, in fact, in was more of a necessity. While TPN does provide essential nutrients when the gut can’t, it doesn’t fix the underlying cause of intestinal failure in EDS patients: It’s a management strategy, not a cure. For those who haven’t reached the point of requiring TPN but still struggle with maintaining weight, a multidisciplinary approach is essential. Gastroenterologists, dietitians, and even autonomic specialists often work together to help EDS patients tolerate food better.

Common strategies include:

- Small, frequent meals to reduce gastric discomfort.

- Liquid nutrition (high-calorie shakes, blended meals) when solid foods are difficult to tolerate.

- Prokinetic medications to improve gut motility and move food through the digestive tract.

- Feeding tubes (nasogastric or jejunostomy) for those who can’t sustain weight with oral intake.

Eating disorders and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS)

Eating disorders and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS) have a complicated and often misunderstood relationship. While eating disorders are typically thought of as psychiatric conditions, individuals with EDS often develop disordered eating behaviors that are deeply rooted in physical dysfunction rather than psychological causes alone. The intersection of gastrointestinal (GI) dysfunction, autonomic dysregulation, chronic illness-related trauma, and psychological distress creates a perfect storm that places those with EDS at an alarmingly high risk for both true eating disorders and secondary disordered eating patterns. However, because of the overlap in symptoms, EDS patients are frequently misdiagnosed, either having an eating disorder they don’t actually have or struggling with one that goes unrecognized due to their medical complexities.

Research shows that individuals with EDS, particularly hypermobile EDS (hEDS), have a significantly higher prevalence of eating disorders compared to the general population. In a study of 681 patients with hEDS, 17.3% reported having an eating disorder diagnosis at some point in their lives. Compare that to the general population, where the lifetime prevalence of eating disorders is approximately 8.4% in women and 2.2% in men, and the connection becomes glaringly obvious. Another study comparing women with EDS to healthy controls found that those with EDS were far more likely to exhibit disordered eating behaviors, have a history of an eating disorder, and have a lower body mass index (BMI). But what makes the risk so much higher in EDS? The answer lies in a complex mix of chronic GI issues, pain, trauma, and autonomic dysfunction that make food a source of distress rather than nourishment.

For many with EDS, eating itself is physically painful and uncomfortable. Gastroparesis, leads to early satiety, bloating, nausea, and vomiting. Dysmotility affects the entire digestive tract, meaning food lingers too long, causing pain, reflux, and distension. Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS), which commonly coexists with EDS, can trigger nausea, dizziness, and blood pooling that worsens after meals. The result is that many develop restrictive eating habits—not out of fear of weight gain, but out of fear of the physical misery eating brings. This is why restrictive eating patterns in EDS must be carefully examined before assuming they stem from a primary eating disorder. Many people with EDS aren’t restricting because of body image concerns, but because their bodies punish them for eating.

The misdiagnosis risk here is substantial. Many adolescents with hEDS present with severe weight loss, low appetite, and avoidance of food and are immediately labeled as having anorexia nervosa or Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID). While true eating disorders exist in the EDS population, many are actually experiencing severe GI dysfunction that mimics an eating disorder but has a completely different underlying cause. When these patients are placed in eating disorder treatment centers without proper medical evaluation, their physical suffering is dismissed as an extension of their “food avoidance,” and the real issue, GI dysmotility, pain, or autonomic dysfunction, is left untreated. This can lead to inappropriate forced refeeding, accusations of non-compliance, and a failure to address the root cause of the problem.

On the other hand, EDS can also contribute to the development of true eating disorders. Anxiety and depression, both of which are highly prevalent in EDS, increase vulnerability to restrictive eating, binge eating, and other maladaptive food behaviors. Trauma is another major risk factor—many EDS patients report childhood bullying due to their visible symptoms (bruising, scarring, joint deformities, or thin stature), which contributes to poor body image and disordered eating behaviors. There are also cases where EDS patients with gastrointestinal distress and weight loss are praised for their thinness—reinforcing restrictive eating patterns that then spiral into a full-blown eating disorder. In some cases, long hospitalizations, tube feeding, and medical trauma around nutrition cause patients to develop a fear of food or medical distrust that later manifests as an eating disorder.

The issue of binge eating and uncontrolled eating behaviors in EDS is also worth addressing. While restrictive eating patterns dominate the conversation, some patients with EDS experience binge eating linked to autonomic dysfunction, emotional distress, or disordered hunger cues. Autonomic dysregulation affects ghrelin and leptin hormones that control hunger and satiety—leading to erratic hunger signals. Additionally, chronic pain, fatigue, and depression often contribute to emotional eating patterns, as food becomes one of the few accessible coping mechanisms. Some people with EDS struggle with dysregulated hunger cues due to gastroparesis, where they may eat very little for extended periods and then experience extreme hunger, leading to binge episodes. This cycle of restriction and bingeing can be damaging both physically and mentally and is often overlooked in EDS care.

The treatment of eating disorders and disordered eating in EDS patients must be multifaceted and take into account both physical and psychological components. A patient with gastroparesis and malnutrition should not be treated the same as a patient with primary anorexia nervosa, but they still need structured nutrition support, medical monitoring, and sometimes psychological intervention. For those with underlying GI dysfunction, the focus should be on finding ways to make eating more tolerable, such as adjusting meal sizes, using prokinetic medications, or switching to enteral feeding if necessary. In contrast, for those with anxiety-driven restriction, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can help reduce food-related fears. The key is recognizing that not all disordered eating in EDS is psychological, and not all psychological eating disorders in EDS are purely mental.

A multidisciplinary approach is crucial. Gastroenterologists, dietitians, mental health professionals, and autonomic specialists must work together to develop an individualized plan that addresses the root cause of eating difficulties.Nutritional rehabilitation should be approached carefully, for those with motility disorders, increasing caloric intake too quickly can worsen symptoms, and for those with true eating disorders, the psychological barriers to food must be addressed alongside refeeding. Additionally, there must be an increased awareness among clinicians that restrictive eating behaviors in EDS are often secondary to underlying medical conditions….not always signs of a primary eating disorder.

The connection between EDS and eating disorders is far from straightforward, as for some, it’s a matter of GI dysfunction forcing them into disordered eating patterns. For others, it’s years of trauma, anxiety, and body image issues manifesting in food restriction. And for many, it’s a combination of both, creating a complex situation that requires careful, individualized treatment. The biggest danger comes when EDS patients are misdiagnosed and either denied care for a real eating disorder or forced into inappropriate treatment for one they don’t actually have. The solution isn’t to assume that all EDS patients with disordered eating habits have an eating disorder, but it’s also not to assume that they don’t. Careful assessment, medical awareness, and a willingness to see the whole picture, (not just the symptoms) are what will ultimately lead to better outcomes for those struggling at this difficult intersection of chronic illness and disordered eating.

Common Medications That Can Cause Weight Gain

Chronic pain is one of the most debilitating aspects of EDS, and for many, neuropathic pain medications are the only way to function. But these drugs don’t just dull pain, they also mess with appetite, metabolism, and fluid balance.

Gabapentin & Pregabalin (Lyrica):

These are commonly prescribed for neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and anxiety in EDS. While they can be highly effective, they’re notorious for causing weight gain. Research shows they can increase appetite and lead to fluid retention, making weight fluctuations common. Some patients report gaining weight rapidly within the first few months of use.

Opioids:

Though not the first line of treatment in EDS, some people are prescribed opioids for severe pain. While they don’t directly cause weight gain, their sedative effects can reduce activity levels, leading to muscle loss and metabolic slowdown.

Beta Blockers (Atenolol, Metoprolol):

Older beta blockers slow down metabolism, meaning the body burns fewer calories throughout the day. They also contribute to fatigue and reduced energy levels, making exercise harder. Some people also experience fluid retention, which adds to weight gain that isn’t necessarily due to fat storage.

Fludrocortisone (Florinef):

Often prescribed for low blood pressure in POTS, this medication increases sodium retention, which can lead to bloating and fluid-related weight gain.

Antihistamines (H1 blockers like cetirizine, H2 blockers like famotidine):

While essential for controlling MCAS symptoms, some antihistamines increase appetite and contribute to fluid retention. Long-term use of certain antihistamines has even been linked to metabolic changes that make it harder to lose weight.

Steroids (short-term use for inflammation or severe MCAS reactions):

If you’ve ever had to take prednisonefor a severe flare, you’ve probably noticed rapid weight gain due to increased appetite and fluid retention. While this is usually temporary, frequent steroid use can alter metabolism over time.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors & Tricyclic Antidepressants:

Some antidepressants are known to increase appetite, change metabolism, and cause fluid retention.

Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam, lorazepam):

Used for severe anxiety or muscle spasms, these drugs slow down the nervous system, often leading to fatigue, reduced activity, and weight gain.

Why Do These Medications Affect Weight?

Weight gain from medication isn’t just about “eating more.” It’s caused by a combination of metabolic changes, increased appetite, fluid retention, and reduced energy levels.

Increased Appetite:

Many medications, particularly gabapentin, pregabalin, and antihistamines, can affect neurotransmitters that regulate hunger: leading to feeling hungrier than usual, craving more food, and struggling with portion control.

Fluid Retention:

Beta blockers, opioids, and certain antihistamines can cause bloating and swelling that makes weight fluctuate, even without eating more. This kind of weight gain isn’t fat, but it still feels frustrating non the less.

Metabolic Slowdown:

Medications like beta blockers reduce energy expenditure, meaning you burn fewer calories at rest. Over time, this can lead to gradual weight gain, even if your diet stays the same.

Sleep, Fatigue, and Weight in EDS

If you ask any of my clients, they will tell you just how much emphasis I place on good sleep, when it comes to rehab. Most people know sleep is important, but they don’t really understand just “how” important it is, and what happens when you don’t get good sleep. In fact, it such a big topic for me that I easily poured out 8000 words on the topic in our hypermobility and sleep article, so check it out if you want to go deeper.

Essentially, poor sleep messes with everything, from metabolism and hunger signals, to pain sensitivity and energy levels. It’s a cycle that’s hard to break, but understanding the connection between sleep, fatigue, and weight changes in EDS can help make sense of why it’s happening, and what can be done about it.

Poor Sleep Wreaks Havoc on Metabolism

For most people, sleep is the body’s chance to reset, hormones regulate, focus on tissues repair, and the nervous system gets a chance to recalibrate. But when you have Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), sleep doesn’t always do what it’s supposed to. Instead of waking up feeling refreshed, many people with EDS wake up feeling just as exhausted as when they went to bed.

And it’s not just about feeling tired. Research shows that up to 61% of people with EDS report poor sleep quality, with 68% waking up unrefreshed, no matter how many hours they get. This isn’t just frustrating; it has real metabolic consequences.

Poor sleep throws hunger hormones completely out of balance. Ghrelin, the hormone that makes you feel hungry, goes up, while leptin, the hormone that tells you you’re full, goes down. That means you feel hungrier, crave more food, and struggle to feel satisfied after eating. On top of that, cortisol levels spike, promoting fat storage (especially around the abdomen) and making it harder for your body to process glucose. Over time, this leads to weight gain, increased inflammation, and energy crashes that make everything feel harder.

And if that wasn’t enough, insulin resistance worsens when deep sleep is constantly disrupted. This means your body struggles to convert food into energy efficiently, leaving you feeling fatigued but storing more fat. It’s no surprise that so many people with EDS experience both constant exhaustion and unexplained weight changes at the same time.

Pain & Disrupted Sleep

If there’s one thing guaranteed to ruin a good night’s sleep, it’s pain. And if there’s one thing that makes pain worse? Yep, bad sleep.

Chronic pain keeps the body stuck in lighter sleep stages, preventing the deep, restorative sleep that’s needed for healing and hormonal regulation. This means higher cortisol levels, increased pain sensitivity, and worsened inflammation. And once sleep is disrupted, pain perception actually increases, making even mild discomfort feel unbearable.

Over time, this creates a never ending loop: pain disrupts sleep, and poor sleep amplifies pain. And because restorative sleep is crucial for metabolic function, this cycle also leads to increased cravings, slowed metabolism, and even greater difficulty managing weight.

EDS, poor sleep, fatigue, and weight changes are all connected. It’s not just about not getting enough hours, it’s about the quality of sleep, the impact of pain, and the exhaustion that comes with a body that’s constantly in survival mode.

If you’ve been struggling with unexplained weight gain, relentless fatigue, and the inability to stay active, it’s not your fault. Your body isn’t just being difficult, it’s reacting to real, physiological imbalances that make weight regulation harder than it should be.

Next Steps

If there’s one thing I always tell my clients, it’s this: start with sleep.

Why? Because when sleep improves, so does everything else. Pain feels more manageable, energy levels increase, hunger signals regulate, and the body gets a better chance to heal. And let’s be real, if you’re running on exhaustion, everything else feels ten times harder.

So, if you’re looking for the first step in tackling weight challenges with EDS, focus on getting better sleep. If you haven’t already, check out our Hypermobility and Sleep blog, it’s an 8,000-word deep dive into exactly why sleep matters, how to improve it, and why so many people with EDS struggle to get restorative rest. Also, take a look at the video below, where I go through finding a good sleep position that actually supports hypermobile joints.

Once sleep starts improving, you’ll have more bandwidth to focus on everything else, like diet, movement, and nervous system regulation. And when it comes to exercise, the best place to start isn’t with strength, it’s with cortical mapping.

Forget the “just build muscle” advice, if your brain doesn’t know where your joints are in space, it won’t be able to use your muscles properly anyway. That’s why so many people with EDS feel unstable or keep getting injured despite working on strength. Mapping first, movement second.

If you want a breakdown of how to get started, check out our Hypermobility and Exercise article, it covers exactly why cortical mapping matters and how to retrain your brain to actually control movement again.

Weight challenges in EDS are complex: they’re not just about diet or exercise, but about pain, sleep, gut health, and nervous system function. The key is tackling the foundational issues first, sleep, nervous system regulation, and pain management, so that everything else becomes easier to work on.

You don’t have to work on everything overnight, and you definitely don’t have to do it alone. Start small, focus on what’s in your control, and build from there. And if you’re feeling overwhelmed, take a deep breath, you’ve got this.

FAQ On EDS and Weight Management

No, EDS itself does not directly cause weight gain. However, its symptoms, such as chronic pain, fatigue, and joint instability, often lead to reduced physical activity, which can indirectly contribute to weight gain. Additionally, autonomic dysfunction and gastrointestinal issues associated with EDS may alter metabolism or eating behaviours.

Source: Frontiers in Neurology – Overview of EDS and Associated Conditions.

Individuals with EDS often experience joint instability, chronic pain, and fatigue, which make traditional forms of exercise challenging or even harmful. Fear of injury (kinesiophobia) and fatigue further discourage physical activity, leading to deconditioning and reduced mobility over time.

Source: Exercise and Rehabilitation in Individuals with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

GI symptoms such as gastroparesis (delayed stomach emptying), dysmotility, constipation, and reflux are common in EDS. These issues can lead to irregular eating patterns or reliance on calorie-dense foods that are easier to digest. In some cases, malabsorption or discomfort after eating may result in unintentional weight loss instead of gain.

Source: Pharmaceutical Journal – Gastric Problems in EDS.

Yes, certain medications commonly prescribed for managing EDS symptoms—such as gabapentin, pregabalin, antidepressants, or steroids—can have side effects like increased appetite or metabolic changes that promote weight gain. These medications are often necessary for symptom management but may complicate weight control efforts.

Source: Pain Physician Journal – Medication Side Effects in EDS.

Yes, living with a chronic condition like EDS can lead to anxiety or depression, which may result in emotional eating or binge eating behaviors. Additionally, the psychological burden of managing a complex condition can influence eating habits and overall health.

Source: Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome in the Field of Psychiatry.

Diet plays a crucial role in managing both symptoms and weight for individuals with EDS. High-fiber foods can alleviate constipation, while nutrient-dense meals help address deficiencies common in EDS patients (e.g., vitamin D or magnesium). Tailored dietary plans are essential to avoid exacerbating GI issues like bloating or gastroparesis while maintaining proper nutrition.

Source: PMC – Gastrointestinal Problems and Eating Disorders in EDS.

Yes, but it requires a carefully managed approach:

Low-impact exercises like swimming or yoga are often recommended.

Collaboration with dietitians familiar with EDS is crucial for creating sustainable dietary plans.

Addressing comorbidities like Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is also key to improving overall health and facilitating safe weight loss.

Source: Exercise and Rehabilitation in People With Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Bariatric surgery is typically considered a last resort due to the risks associated with connective tissue fragility and healing complications in EDS patients. However, it has been successfully performed under strict medical supervision in specific cases where other interventions failed.

Source: Obesity Surgery and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Yes, individuals with EDS are prone to deficiencies in:

– Vitamin D: Important for bone health.

– Magnesium: Helps reduce muscle cramps.

– Iron: Essential for managing fatigue caused by anemia.

– Monitoring these nutrients is critical for overall well-being, especially since GI issues can interfere with absorption of these key vitamins and minerals.

Source: Pharmaceutical Journal – Calcium and Vitamin D in EDS.

Obesity may increase lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD), but it does not necessarily protect against conditions like osteoporosis or osteopenia that are common in EDS due to connective tissue fragility. Excess weight can also worsen joint instability and pain, further complicating mobility issues in this population.

Source: Endocrine Abstracts – Obesity and Bone Mineral Density in Women with EDS.