- POTS and Exercise: The First Step Everyone Misses - 27 June 2025

- The Missing Link Between Breathlessness, Fatigue, and Chronic Pain: Understanding CO₂ Tolerance - 19 June 2025

- What is Mast Cell Activation Syndrome? - 12 May 2025

You’re not alone if you’ve ever been perplexed by the fact that your joints can bend in ways that make your buddies squirm, but you still find it difficult to perform a simple toe-touch stretch.

It’s a confusing scenario, isn’t it? On one hand, you’ve got hypermobile joints that seem to have an impressive range of motion. But on the other, your muscles feel tight, restricted, and anything but flexible.

So, what’s going on here?

Although the terms hypermobility and flexibility are frequently used interchangeably, they are actually not the same. Many people may become irritated by this misconception, particularly if they are putting a lot of effort into increasing their mobility and are not getting the desired results.

We’ll go into the subtleties of these two concepts in this blog, examining their true meanings, their differences, and the reasons why you could be hypermobile but not very flexible.

This post is for everyone, whether you’re a professional attempting to support someone with these issues, an inquisitive fitness enthusiast, or someone navigating life with hypermobile joints.

This article covers:

ToggleUnderstanding Hypermobility and Flexibility

Hypermobility is the capacity of your joints to move outside of what is regarded as a “normal” range of motion. Your ligaments and connective tissues, which are the structures that hold your joints together, have a major role in determining how loose they are. You may have heard of the Beighton Score, a popular test that measures how much a joint can bend to determine hypermobility.

What is the Beighton score?

The Beighton Score is one of the most popular instruments in clinical settings for evaluating hypermobility. Dr. Arthur Beighton created this straightforward nine-point scoring system in the 1970s to gauge the level of joint hypermobility in several important body parts.

The Beighton Score’s Five Tests:

- Passive Dorsiflexion of the Little Finger: Can your little finger bend backward beyond 90 degrees? (1 point per hand)

- Passive Apposition of the Thumb: Can your thumb touch your forearm when bent backward? (1 point per hand)

- Elbow Hyperextension: Can your elbows extend beyond 10 degrees? (1 point per elbow)

- Knee Hyperextension: Can your knees extend beyond 10 degrees? (1 point per knee)

- Forward Bend: Can you bend forward with straight legs and place your palms flat on the floor? (1 point)

A score of four or higher is typically regarded as suggestive of generalised joint hypermobility, with a maximum score of nine.

The problem is that it goes beyond simply checking things off a list. The Beighton Score is only one component of a bigger picture. To get a better picture of a patient’s joint health, clinicians frequently combine it with other tests, medical history, and symptom patterns.

For instance, hypermobility may be indicated by a high Beighton Score, but this does not always imply that a person has a disorder such as Hypermobility Spectrum Disorder (HSD) or Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS).

The Beighton Score: Why Is It Important?

You can better understand why your joints behave the way they do by knowing your Beighton Score. Additionally, it can help medical professionals develop customised management plans, such as addressing chronic pain, strengthening and stabilising muscles, or enhancing proprioception.

The Beighton Score can therefore provide important insight if you’ve ever been told that you’re “double-jointed” or if you’ve observed that your body moves in ways that others can’t.

It’s crucial to remember that you can’t force yourself into hypermobility. As with having large feet or long arms, it is a structural trait. It’s either in your possession or not.

How About Adaptability?

Conversely, your muscles and tendons are the key to flexibility. It is these soft tissues’ capacity to elongate and permit motion over a joint’s range of motion. In contrast to hypermobility, regular stretching, mobility drills, and physical conditioning can help increase flexibility.

However, the problematic part is that being hypermobile does not equate to being flexible. On the contrary, hypermobility frequently results in muscles that feel constricted, locked up, and unresponsive to stretching.

Why the Distinction Is Important?

For example, consider hypermobility as the hinges on a door, and flexibility as the rope that is fastened to those hinges. The hinge (your joint) will not move correctly no matter how much extra range it has if the rope (your muscles and tendons) is too weak or too tight.

And there are practical ramifications to this distinction; it is not merely a technicality. Someone may have hypermobile joints in their spine, for instance, but have trouble even touching their toes. Or they may find it difficult to stretch their hamstrings yet have no trouble hyperextending their elbows.

Key Differences Between Hypermobility and Flexibility

Although they may appear to be two sides of the same coin, these two terms frequently have quite different effects on how your body moves, and occasionally they even conflict.

Tightness in the muscles vs joint laxity

The looseness or stretchiness of the connective tissues that keep your joints together is the fundamental component of joint laxity, which is the essence of hypermobility. Your tendons and ligaments can be thought of as elastic bands. The bands in hypermobility are a bit more elastic than they should be.

On the other hand, the ability of your muscles and tendons to lengthen and permit movement is known as flexibility. In addition, your brain may actually tighten your muscles as a defensive measure if you have hypermobile joints. Your body is telling you to wait since things are a little shaky. To prevent anything from going wrong, let’s lock this down.

A strange contradiction arises when you have the anatomical capacity to move farther but the functional incapacity to do so. Hypermobility allows your joints to move more freely, but muscular stiffness can limit your range of motion.

Mobility vs. Stability in Movement Types

The kinds of movement to which each phrase alludes is another important distinction. Passive movement is made possible by hypermobility, such as when someone pushes your leg into a spectacular split. Active movement, such as controlling your leg as it moves into that split on its own, is made possible by flexibility.

In other words, whereas flexibility allows you to take control of the movement, hypermobility allows your body to go there. When such hypermobile joints are not controlled by strength and flexibility, motions may seem shaky, uncomfortable, or unstable.

Traditional stretching exercises are frequently ineffective or even harmful for people with hypermobility for this reason. It’s not always beneficial to increase passive stretching if your joints are already moving outside of their natural range. Instead, strength and stability training is frequently required.

Injury Risks, Different Causes, Different Outcomes

In terms of injury hazards, inflexibility and hypermobility present somewhat different difficulties.

Muscle strains are a common source of injury for inflexible people, the quintessential “I stretched too far” situation. However, injuries are more likely to result from joint instability in hypermobile individuals. Subluxations, dislocations, and overuse injuries can result from joints that have loose ligaments because they may not remain firmly in place when moving.

If you are both hypermobile and inflexible, which is totally possible, your body is simultaneously juggling two conflicting demands. This is where things get complicated.

By keeping your muscles taut, your brain tries to lock down unstable joints, but this restricts your range of motion and forces your body to compensate in other regions. And those payouts? In other words, they frequently turn into havens for pain and harm.

Why You Should Care About This

Knowing these distinctions is useful in real-world situations as well as academic ones. If you’re treating your body as though flexibility and hypermobility are synonymous, you may be unintentionally working against rather than with it.

For instance, vigorous stretching might not be the solution if your joints feel loose and your muscles feel tight. It might further worsen the situation. Instead, you may be able to unlock greater ease and comfort in your body by developing strength, stability, and body awareness through deliberate movements.

We’ll look at the specific reasons why someone could be hypermobile yet not flexible in the next part, along with additional crucial solutions.

Why Someone Might Be Hypermobility but Not Flexible

As we’ve shown so far, hypermobility and flexibility are two entirely different concepts. The former refers to the range of motion that your joints can achieve, while the latter measures how well your muscles and tendons permit that movement. However, what causes so many hypermobile people to experience a sense of tightness, rigidity, or restriction in their range of motion? It seems illogical, doesn’t it?

Protective Muscle Guarding: Your Brain on High Alert

Your brain acts as an amazing shield. When it senses something that feels unsafe, such as a hypermobile joint wobbling around, it tightens the surrounding muscles. It continuously scans your body for indications of instability.

It is comparable to a security system. When your brain detects a potential dislocation or subluxation of a joint, it signals your muscles to “lock this down.” Protect it. Avoid letting it go too far.

What was the outcome?

Muscles that are overworked and tense, doing everything they can to make up for loose ligaments. Despite your ability to bend your joints into extreme positions, this guarding can cause a persistent sensation of muscle tension.

Because of this, even though hypermobile people’s joints can still move into impressive ranges, they frequently feel tight in places like their neck, shoulders, or hamstrings. It is a neurological lockout that is intended to keep you safe, not a lack of flexibility.

Neurological Factors

Proprioception is another mechanism that your brain uses to prevent instability in addition to muscles. This is your body’s sense of location in space, and it is mostly managed by microscopic receptors found in your joints, muscles, and tendons.

The issue is that hypermobile joints frequently give the brain jumbled signals. When joints move around and ligaments are a bit too supple, the brain doesn’t always receive accurate, clear information about what’s going on in your body.

And your brain clamps down, just like any good security guard would, when it doesn’t trust your joints. Your muscles are called upon to perform the function that your ligaments are finding difficult.

What was the outcome?

Less functional flexibility, more tense muscles, and a body that feels like it’s fighting itself.

Lifestyle Factors: A Vicious Cycle of Inactivity and Fear

A person’s lifestyle is another important factor that may contribute to their hypermobility but lack of flexibility.

For a lot of hypermobile individuals, moving can feel dangerous. If you have previously suffered from a joint subluxation, dislocation, or injury, it is quite reasonable for you to begin to avoid specific movements, or even movement altogether.

The problem is that muscles that aren’t used frequently get shortened and taut. Strength is only one factor; the quality of the muscle tissue itself is also important.

In a similar vein, your movements may eventually become more controlled, smaller, and stiffer if you’re always protecting yourself from injury. Although this might feel safer in the short term, it can result in underused and poorly supported joints and muscles that are always tight.

A vicious cycle is in place:

- Guarding of muscles is triggered by joint instability.

- Muscle guarding makes the muscles tight.

- Tightness inhibits mobility.

- More instability results when there is no movement.

- We continue to go around and round.

Fear and Pain: The Invisible Barriers to Flexibility

Pain should not be overlooked because, when it comes to hypermobility, it frequently speaks loudest.

Your brain will recall if there has previously been pain when assuming particular positions. It also prevents you from re-entering those positions without resistance.

Because it is a neurological barrier rather than a physical one, this defence mechanism cannot be easily removed.

For this reason, hypermobile people frequently find that traditional stretching exercises are insufficient. You’re fighting against more than just tense muscles; you’re fighting against your brain’s actual fear of getting hurt.

What are your options?

Fortunately, this mismatch between flexibility and hypermobility can be addressed. It’s important to work with your nervous system, not against it, rather than pushing your body into deeper stretches.

The secret, for many, is in:

- Bolstering hypermobile joints with stability and strength.

- Avoiding passive stretching in favour of deliberate, controlled motions.

- Restoring your brain’s trust in your body and enhancing proprioception.

We’ll go over how to approach movement, exercise, and stretching in a way that promotes both hypermobility and flexibility in the next section, without causing discomfort, anxiety, or additional instability.

Practical Advice

For people who are hypermobile, stability should be prioritised over just bulky muscle growth. Strength alone won’t give hypermobile joints the support they require.

Important Principles for Stability Training:

- Isometric Exercises: These entail maintaining a posture while not moving, such as wall sits or planks. They can lower the risk of subluxations by increasing strength and stability without causing excessive joint movement.

- Closed-Chain Exercises: Exercises like push-ups and squats that require the hands or feet to be fixed to a stable surface give the brain clear proprioceptive feedback while lowering the risk of instability.

- Progressive Loading: Although resistance and weights can be used, they should be added gradually, and the emphasis should be on control and accuracy rather than heavy lifting.

Why Stability Matters:

By teaching the nervous system and muscles to support joints consistently, stability exercises lessen the need for hypermobile ligaments to maintain structural integrity.

Proprioception: Training the Brain to Trust the Body

Lax ligaments and disturbed sensory feedback frequently cause hypermobile people to have impaired proprioception, or the brain’s ability to sense where the body is in space.

Ways to Improve Proprioception

• Small, Controlled Movements: Put more emphasis on slow, intentional movements that increase joint position awareness rather than big, sweeping motions.

• Balance and Stability Drills: Proprioceptive feedback can be improved with exercises like single-leg stands, stability ball drills, or mild wobble-board work (when safe).

• Tactile Feedback: The brain’s comprehension of joint positioning can be enhanced by lightly touching a joint while moving (for example, putting a hand on the knee during a squat).

Why Proprioception Matters:

By decreasing needless muscle guarding and improving overall movement quality, improved proprioception aids the brain in trusting the body’s movements.

By putting additional strain on already weakened ligaments, passive stretching, which involves pushing joints to their limit and holding them there, can sometimes exacerbate hypermobility. Instead, concentrate on exercises for active mobility.

Safe Stretching Strategies:

- Active Stretching: Engage muscles while moving into and holding a stretch. For example, actively lifting the leg into a stretch rather than pulling it with your hands.

- Dynamic Stretching: Repeated, controlled movements (e.g., gentle leg swings) improve flexibility without destabilizing joints.

- Controlled End-Range Training: Build strength and stability at the furthest point of your range of motion to ensure it’s functional and safe.

Why Active Stretching is Better:

Active stretching focuses on muscle engagement rather than ligament stress, providing flexibility that’s supported by strength.

Address the Subluxation/Dislocation Cycle:

The cycle of joint subluxation or dislocation followed by guarding, inactivity, and further instability is one of the most annoying problems for hypermobile people.

Breaking the Cycle:

- Start Small: To prevent causing instability, start with low-risk, low-load movements.

- Address Muscle Guarding: Reduce overactive protective reflexes by using slow, deliberate movements and gentle breathwork.

- Avoid Fear-Based Movement Patterns: Compensatory movement patterns brought on by a fear of subluxation frequently make instability worse. Confidence is developed through gradual exposure to safe movement.

- Controlled Exposure: Gradually add bigger or more intricate movements while maintaining constant attention to safety and control.

Long-term dysfunction brought on by persistent guarding and instability can be avoided by breaking the subluxation cycle.

Nervous System Calming

The way that muscles respond to hypermobility is greatly influenced by the nervous system. Its protective reaction is to tighten muscles when it detects instability. This guarding is frequently confused with tight muscles, which results in inappropriate treatment methods.

Techniques to Calm the Nervous System:

- Diaphragmatic Breathing: Deep, slow breaths ease tension in the protective muscles and lessen hypervigilance of the nervous system.

- Mindful Movement: Practicing exercises with intention and focus lowers anxiety and facilitates more fluid motor control.

- Gradual Progression: Pushing too quickly or too hard can set off alarms in the nervous system. The race is won by being slow and steady.

Why the Nervous System Matters:

Muscle guarding reduces, proprioceptive feedback improves, and controlled movement is made easier when the nervous system feels secure.

Sensory Feedback and Cortical Mapping:

The brain receives continuous information about joint position, muscle tension, and movement from sensory nerves, such as cutaneous nerves, nociceptors, and mechanoreceptors. Hypermobility, however, may result in erratic or hazy signals.

Improving Sensory Feedback:

- Consistent Movement Practice: Regular, low-intensity movement practice helps the brain retrain itself to correctly interpret sensory input.

- Avoid Overreliance on One Sensory System: To develop a comprehensive sense of body awareness, balance the input from tactile cues, vestibular feedback, and vision.

- Neuromuscular Training: Activities that combine movement and sensory input, such as light resistance training and balancing exercises, aid in the improvement of cortical maps.

Rest and Recovery Tips:

- Prioritize Quality Sleep: Sleep is necessary for tissue repair and nervous system regulation.

- Pace Your Activities: Don’t put too much strain on your nervous system and joints at once. Throughout the day, spread out your activities.

- Gentle Movement on Rest Days: Mobility exercises, walking, or light stretching maintain muscle engagement without being taxing.

If this blog has taught you anything, it’s that your body isn’t broken and doesn’t require repair; rather, it just requires understanding.

Many people with hypermobility find it frustrating when they are told to “be careful,” “stretch more,” or “move less.” However, those general suggestions completely miss the mark. They ignore the delicate equilibrium your body is attempting to preserve, where flexibility, strength, and stability must all coexist.

Your Body Wants to Feel Safe

Every topic we’ve covered, from tightness to brain signals to muscle guarding, has one fundamental theme: safety. Your brain doesn’t trust your joints, so it tightens muscles. It avoids some stretches out of fear of getting hurt.

The good news is that trust can be restored.

Your body can regain its ability to move confidently with strength training, deliberate movement, and mild exposure to safe stretches. Even though it won’t happen right away, every little step you take counts.

Celebrate the Small Victories:

Hypermobility progress isn’t always linear. There will be days when you feel like you’re moving forward at a tremendous pace, and other days when you feel like you’re stagnating or even regressing. And that’s all right.

Perhaps after stretching today, you felt less tension in your shoulders. Perhaps you made a little more progress yesterday in a controlled, safe movement. Those victories matter. They are proof that your body is paying attention, changing, and regaining its self-confidence.

No one-size-fits-all strategy exists.

All hypermobile bodies are different. A customised approach is crucial because what works for one individual may not work for another. If you’ve been feeling frustrated by generic advice, know that the problem is with the advice, not with you.

It may take some trial and error to find a plan that works for you, and that’s okay. There is a place for proprioception drills, mild mobility work, and strengthening exercises. But patience is the most crucial component.

Knowledge is Power.

Congratulations to you if you have read this far in the blog. You’ve equipped yourself with information that will form the basis of your future movements, training, and body care regimen.

Because ultimately, the most effective tool you have is your understanding of your body.

You now understand:

- Hypermobility and flexibility are not the same.

- Muscle guarding and brain signals play a huge role in how your body feels.

- Stretching isn’t always the answer—sometimes, strength and stability come first.

- Proprioception and neurological trust are key players in improving mobility.

Know that you can make progress whether you’re starting from scratch, getting better from an injury, or perfecting your exercise regimen. Every step matters, even though it might not always seem like the straight path you had in mind.

Hey, you’re not travelling this path alone. There is an entire community of people who are facing the same difficulties, rejoicing in the same successes, and posing the same queries.

I’d love to know if this blog struck a chord with you or if you’ve experienced any epiphanies of your own. Leave a remark, tell us about your experience, or contact us with any enquiries.

Because ultimately, improving one’s movement is more important than simply increasing it. With courage, with self-assurance, and above all, without fear.

Be careful, keep going, and never forget that you can succeed.

The Team Fibro Guy

Enjoyed Our Blog? Why Stop Here?

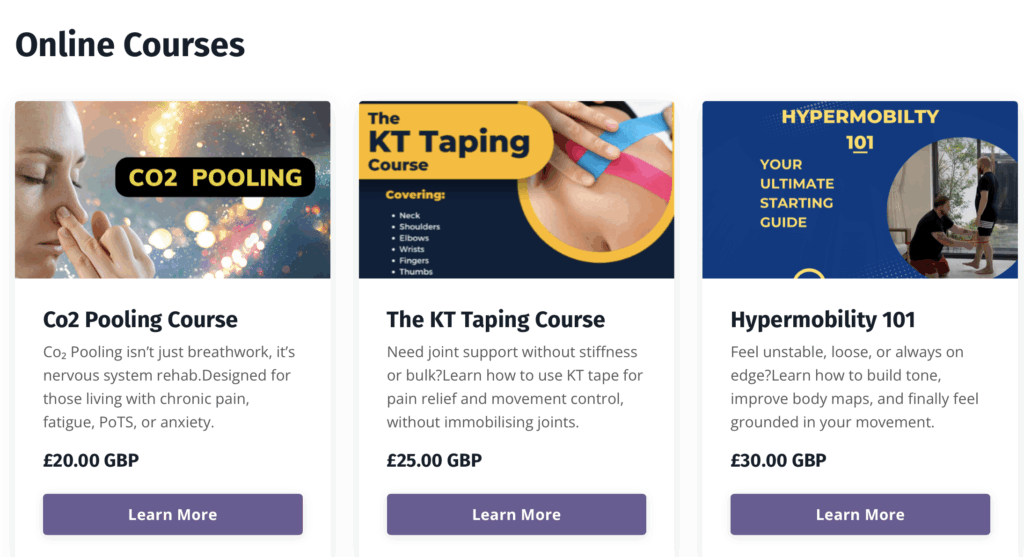

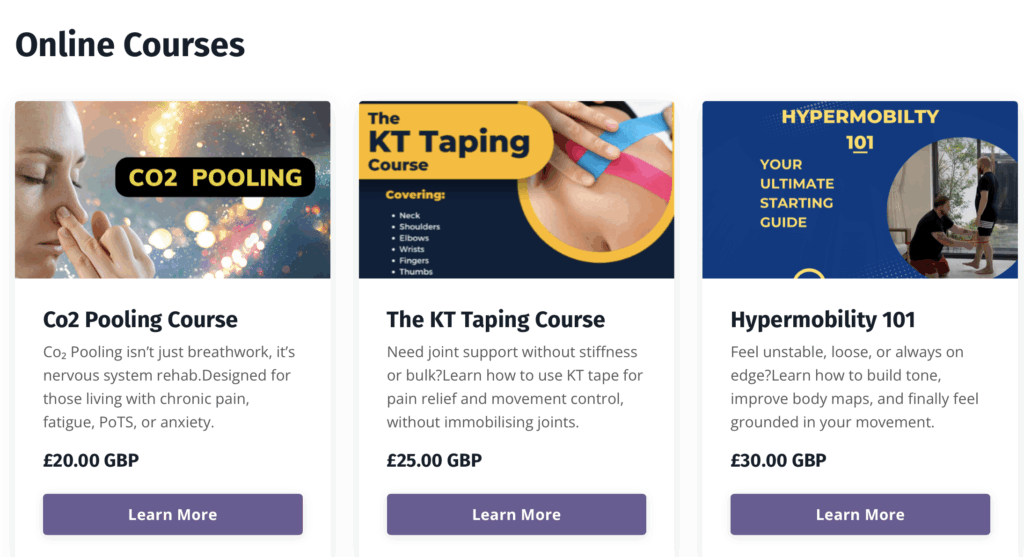

If you’ve found value in our posts, imagine what you’ll gain from a structured, science-backed course designed just for you. Hypermobility 101 is your ultimate starting point for building strength, stability, and confidence in your body.