- POTS and Exercise: The First Step Everyone Misses - 27 June 2025

- The Missing Link Between Breathlessness, Fatigue, and Chronic Pain: Understanding CO₂ Tolerance - 19 June 2025

- What is Mast Cell Activation Syndrome? - 12 May 2025

Chronic back pain is a problem that many people diagnosed with Fibromyalgia deal with on a daily basis, with some studies showing that potentially up to 50% of those diagnosed have back pain.

However, it is not just those with Fibro, chronic back pain affects people all over the world and is now one of the leading causes of disability. The Global Burden of Disease studies the leading causes of years lived with disability, and low back pain has been the number 1 cause since 1990, affecting 7.5% of the world population at any time. Despite the best efforts of the healthcare community and researchers, back pain has become more prevalent over time, and despite an ever-growing body of research into back pain, we still aren’t exactly sure what the causes or the mechanisms behind it are.

In this article, I would like to take a dive into the topic of back pain and Fibromyalgia. This is an area fraught with misinformation, bad science, bias and some really conflicting evidence and guidelines.

As you will find in the paragraphs to come, the overwhelming majority of chronic back pain isn’t down to anything nefarious, however, there are some red flags that we should look out for. So, let’s take a look into the common myths about back pain, treatments, potential causes, and where the research stands.

This article covers:

ToggleDiagnosing Back Pain With Fibro

For many with Fibromyalgia, frustration can be caused when healthcare professionals come back with the inevitable diagnosis of “non-specific low back pain”. This essentially means that they don’t know the precise cause of the pain. However, this doesn’t mean that the care provided is inadequate or pulling a fast one: pain is just complicated, a lot like people!

Likewise, the same is true for other diagnoses such as patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS), which roughly translates to pain in the front of the knee. Telling the doctor your knee hurts often leads to a diagnosis of PFPS, essentially diagnosing you with the same complaint you came in with, just in a fancier way. A lot of issues seem to come with a description of our symptoms, rather than any straight-to-the-point or specific diagnosis of a cause: take Fibromyalgia for instance. This really highlights just how complex pain is and how its causes are multifactorial and almost limitless.

While it is important to try and determine a specific diagnosis, as some cases of back pain (albeit rarely) can be serious, a definitive diagnosis is not always possible. Currently and most common to us as humans, is a strong emphasis on finding a quick solution to the problem, rather than addressing the potential underlying causes of pain.

As someone with Fibromyalgia, you have more than likely found that this approach often relies heavily on diagnostic tools like MRI’s & X-Rays etc. Yet, these treatments often have limited long-term effects and often in the case of surgery, are irreversible.

Out With The Old Back Pain Treatment

If you are reading this then you have almost certainly been through the wringer when being diagnosed with Fibromyalgia. You will most likely already be aware of the standard ways most professionals approach back pain treatment. Most of these current therapies aim to alleviate pain and correct potential structural causes, bulging disks, degeneration, posture, etc.

Spinal adjustments, massage, and posture training are a few of the techniques that healthcare providers may use to help. While these therapies most often come with good intentions, research repeatedly shows that they only offer minor, short-term benefits, and are often clinically insignificant. Likewise, with most treatments, it becomes very apparent from the research that most of the mechanisms driving any relief, if any, are most likely not what is touted by the practitioner.

Many different types of exercises have been created over the years to deal with back pain, ultimately, looking to fix these so-called structural causes of back pain. Most, unsurprisingly, they come with very limited evidence that they are any more helpful than any other type of exercise, and this is something that we will look at in more depth later.

Despite the massive funding for research being thrown at back pain over the years, the current approach to managing chronic back pain just isn’t as effective as it should be. We need to focus on finding evidence-based solutions that address the root causes of the problem, rather than just managing the symptoms, and this is where the problem really lies.

There are many factors at play in the process of deciding whether or not you will produce pain. When we focus on the back, we often lose focus on the person and the myriad of potential pain-driving factors that come with: genetics, work, education, sleep, fear, coping skills, trauma, etc.

Things need to change, and to be honest, they are starting to: it’s just that science is a slow beast.

Busting Myths Around Fibromyalgia And Back Pain

When diagnosed with a chronic pain condition like Fibromyalgia, we tend to turn to the internet for help. Whilst the internet can be a great resource for information and support, it can often be plagued with misinformation. In this section, we will explore some of the most prevalent myths around lower back pain and debunk the bad info.

Myth 1 – Back Pain Means Damage

Pain is a great way to keep a person safe, it is pretty hard to ignore and it makes us really pay attention to it: that’s literally its job. The issue we have is facts and feelings often sit at opposite ends of the spectrum. How we feel is not an accurate representation of what is actually going on in our body, it is just your brain’s interpretation of it.

Think back to the last time you visited the dentist, they likely used something like lidocaine to numb your mouth, so that you could enjoy a filling without screaming in agony: dead thoughtful, dentists.

The sensory nerves in your mouth, lips, and face, were all blocked from talking to your brain.

This rather quick slash in communication results in your brain having to essentially guess how big your lips are, as it is not getting sensory information due to the anaesthetic.

While the brain receives around 11 million pieces of sensory information every second, it does not use all of it. Instead, the brain uses a combination of bottom-up and top-down processing to interpret and make sense of the information it receives. And it can get really adept at filling in the gaps with its own narrative.

Bottom-up processing refers to the brain’s ability to process sensory information arriving from our senses, such as visual or auditory information. The brain takes this and uses it to construct a representation of the world around us.

Top-down processing, on the other hand, refers to the brain’s ability to use our prior knowledge, expectations and context to interpret and make sense of incoming sensory information. For example, if we see a partially obscured object, our brain might use our prior knowledge of that object to “fill in the gaps” and predict what the rest of the object looks like.

Brains work best with both top-down and bottom-up info, and very often when pain is involved, they can under or overestimate just what is happening. Think back to your teenage years and the feeling of a spot coming on just before the big dance. It probably felt like an utter behemoth, but when you looked in the mirror, it wasn’t all the big: your perception was just off. Nothing more than a nervous system being modulated by many factors: in this case inflammation and worry. A true mixture of bottom-up and top-down processing.

The same is true for most back pain: generally, there is no structural cause, and the pain is more so about the nervous system and top-down processing. Factors such as the brain, nerves, immune system and endocrine system can all contribute to our experience of pain. The brain ultimately decides how much pain we experience, and the pain response can persist long after an injury has healed.

It is estimated that 90-95% of back pain has no structural cause. However, it is advisable to look out for any potential red flags, and we will cover these in a little while.

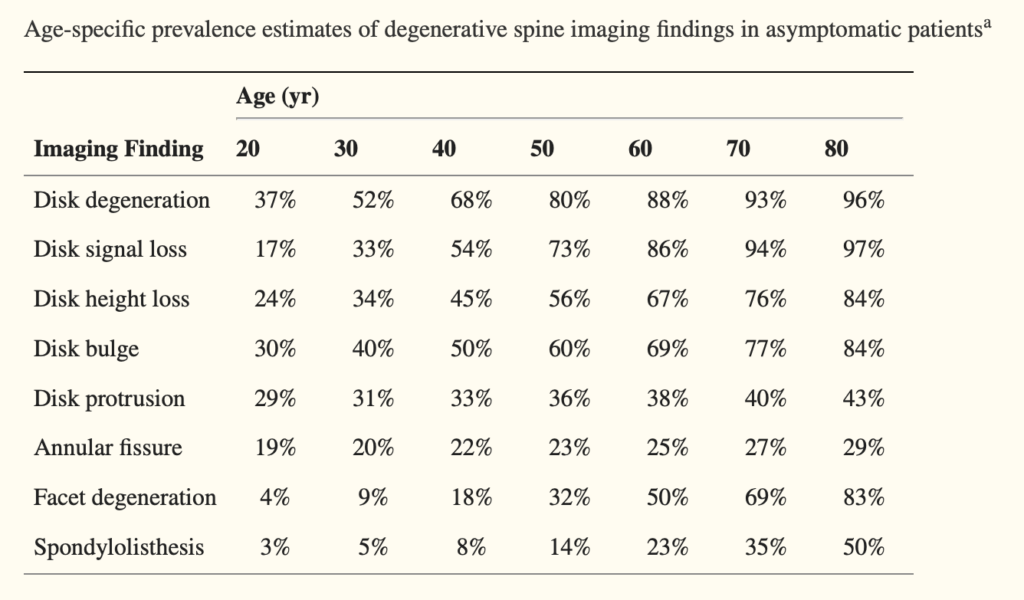

As you can see from the chart below, degenerative changes a very common in people without pain, occurring often more as we age.

Myth 2 – Your Weak Core

The idea that a weak core causes pain has been floating around for years, but it’s actually a myth. Many assumptions have been made over the years about what the “core” actually means, with some people believing that the “Transverse Abdominals (TVA)” is the key to spinal stability. However, the truth is that many different parts of our bodies work together to create stability, including bones, ligaments, muscles and our nervous system. In fact, research shows that there is little evidence to support the idea that a weak core causes pain.

Even pregnant women, who go through huge changes in their bodies, including stretching of the abdominal wall, volumes of the hormone relaxin being released, who you could truly say had “weak cores” showed little evidence that a weak core is the cause of back pain. It is pure lunacy to blame a single tissue in a complex system for causing pain. But alas, here we are!

A favourite study of mine is one of researchers comparing a cognitive-behavioural approach vs standard physiotherapy for pregnant women with back pain. Of the 869 women who participated, 635 of the women dropped out after making a sudden, unassisted, and spontaneous recovery within the first week after giving birth!

Another study compared a core stabilising exercise program without sit-up training to a traditional exercise program and found no significant differences in musculoskeletal injury incidences and work restriction, suggesting that focusing on core strength alone is likely not enough to prevent back pain.

Multiple studies have been done on this topic, and some have found that even if the TVA is damaged, like in some hernia repairs, there is still no strong correlation to pain, showing us that there is still very little evidence that spinal stability plays a part in lower back pain. It just seems to be a myth that will not die.

Does training the core help with back pain?

A few studies, including aimed to compare the effects of core stability exercise versus general exercise for the treatment of chronic low back pain (LBP). The study searched and analysed published articles from 1970 to 2011 that were relevant to the research question. Five trials involving 414 participants were included in the analysis, and the results showed that core stability exercise was better than general exercise in reducing pain and disability in the short term. However, there were no significant differences in pain reduction between the two exercise types in the long term (at 6 months and 12 months). Therefore, this research suggests that core stability exercise may be more effective in decreasing pain and improving physical function in patients with chronic LBP in the short term, but there are no significant differences between core stability exercise and general exercise in the long term.

Some studies say yes; training a weak core is beneficial short term. The likelihood is by doing something physical rather than nothing will yield results, and the associated beliefs around strengthening a “weak core” help the brain in top-down processing by instilling confidence in motion.

Myth 3 – You Slipped a Disc.

One of the most common misconceptions about chronic low back pain is the idea of a “slipped disc.” Research suggests that this is another prevalent and harmful myth. In reality, spinal discs cannot slip. They are anchored in place by the strong endplates of the vertebrae, which create a semi-permeable interface for the exchange of water and solutes. Discs can rupture, causing a herniation or bulge depending on the severity.

There is a difference between a bulge and a herniated disc, however, a lot of people often use the words interchangeably.

A bulge refers to when the outer fibrous ring, the annulus fibrosus, of a spinal disc protrudes beyond its normal range. This can happen gradually over time or as a result of trauma.

In contrast, a herniated disc occurs when the nucleus pulposus, the inner gel-like centre of the disc, extrudes through a tear in the annulus fibrosus. This can cause pressure on the nerves and result in pain, numbness, and weakness in the affected area.

Despite the common belief that herniated and bulging discs are always painful, evidence shows that this is not always the case. Multiple research reviews show that many signs of degenerative spines, bulging discs, protrusions, etc, are very common among people who do not have any pain or symptoms at all, and that these signs become more and more common as people get older.

These signs are generally considered to be part of the normal ageing process rather than a definitive cause of a problem. Even people who are as young as 20 can have some of these signs, but they may not necessarily be causing any symptoms. In fact, previous studies have shown that there is no consistent link between the degree of degeneration seen on imaging scans and the presence or severity of low back pain. This means that doctors need to be cautious when interpreting imaging results and considering treatment options for patients with low back pain and avoid scaring people into inactivity.

Research also shows that the worst things like herniations are, the more likely they are to improve on their own. This goes against common sense and seems like a paradox, but when it comes to fibromyalgia or back pain, there is a lot that goes on. An analysis found that 66% of patients with herniated discs who received conservative therapy, such as physical therapy or medication, had their discs resorb completely by themselves. Another study suggests that discs have the ability to heal without any specific treatment.

Obviously, as we have said before, pain is complicated, which means that whilst bulging or herniated discs may not cause pain or complications for most people, that does not mean for some people it can be a contributing factor in their lived pain experience.

Myth 4 – Bad Posture Causes Back Pain

We often hear people attribute their pain to poor posture. However, this is another idea not backed up by solid scientific evidence.

People with Fibromyalgia are often told that they have poor posture and that correcting it will alleviate their pain. But the truth is, there is no single posture that protects a person from back pain. Research has shown that people with both good and poor posture can experience back pain, and there is little correlation between posture and pain.

Despite the common belief that poor posture causes back pain, numerous studies have found no significant difference in posture between individuals with and without back pain. In fact, the way we stand is highly individual and poorly reproducible, making it difficult to accurately assess posture and identify any issues that may be causing pain.

Research from 2016 found no real difference in lumbar lordosis (spinal curvature) between people with back pain and those without. This is an important research point. If we see something in people without pain, it can not then be solely blamed for causing pain in those who do. Postural assessments are not particularly scientifically valid, as it is difficult to determine which posture is related to the actual problem, and the lack of consistency in standing posture may lead to the wrong diagnosis and probably unnecessary treatment.

In addition, radiological measurements of lordosis are not always reliable, and variations in the shape of people may significantly influence measurements of things like pelvic asymmetry, and everything else that gets thrown at us when it comes to posture.

Another looked at the way people sit and stand and how it affects their spine. Researchers studied 50 people who had no back pain and measured the angle of their spine while they sat at a computer, they were then asked to sit in what they thought was the right posture, and finally in a standing position. The results found that people rarely sit with what we think is a “correct” posture aka; sat up straight. Instead, the angle of their spine while sitting was more bent than while standing.

When people tried to sit with what they thought was the right posture, their spine angle was similar to when they were standing. The study also found that men had a more curved spine while sitting than women, but there was no difference in their spine angle while standing or sitting in what they thought was the right posture.

I think when it comes to posture and pain, especially in those with Fibro, many people get confused between normal posture and prolonged stress: the two are very different.

Posture is really just how we move throughout the day, there really isn’t any one perfect posture as it entirely depends on what we are doing. If you need your shoes from a small under-the-stairs cupboard, then a rounded spine is going to be the best posture. Likewise, if you need something from a high shelf, it’s going to be the worse posture, when compared to a straight or extended spine.

Prolonged positional stress, however, is a different beast entirely. Holding body parts in prolonged positions is just plain uncomfortable, regardless of the body part. We have an inbuilt system that tells us when it’s time to change our position and posture, it is called discomfort and it works pretty damn well. Staying in one position for too long activates high threshold nerves (nociceptors) that detect stimuli which may be potentially harmful: too much pressure, stretch, load, etc. These nerves allow us to avoid getting hurt or damaged by actual or potential threats. Staying in one position for too long changes the blood flow, nerve sensitivity, and tone of the tissue. Ultimately this forces our brain to either say “hey buddy, I think it’s time to move as I need blood” or in some cases “wow, this is dangerous, untold danger, here have some pain so you remember not to do this ever again!” Such is the infinite wisdom of our brain and nervous system.

The point I’m making is if we sit up straight for an hour it will ache, if we slump for an hour, it will ache, it’s not about the position, it’s about the duration. Humans are designed to move, and posture is not very well linked to pain, but prolonged positional stress is, and it’s important to know the difference. Our best posture is our next posture, movement seems to be the best option to avoid holding prolonged positions.

So, What Causes Back Pain?

Whilst non-specific chronic lower back pain is one of the most common conditions and most commonly associated with Fibromyalgia, there isn’t a clear open and shut reason for what causes it, but rather a complex interplay of biological, physiological, and social factors. However, it’s important to note that not all back pain is created equal and sometimes back pain can be specific, and can often be traced back to a specific cause such as an injury or auto-immune conditions.

Sciatica

Sciatica is the loose term for one type of lumbar radiculopathy, essentially meaning pain and other symptoms, caused by irritation of a lumbar nerve root, or at least a part of it. It is also something that seems a lot more prevalent in those with Fibromyalgia, although we are not really sure why. It is also good to keep in mind that sciatica is a symptom, rather than a specific diagnosis, and not a particularly specific one either. The term sciatica can be rather confusing, with many medical professionals using it to describe radiculopathy involving the lower extremities and relating to herniated discs. And many patients refer to sciatica as any pain that shoots down the legs.

There are myriads of ways for the lumbar roots and sciatic nerve to get irritated, including, but not limited to: a nerve pinch, disc herniations and genetic abnormalities. However, it is important to remember that generally, nerve impingement doesn’t cause pain, inflammation does. In fact, the majority of the time, Sciatica is referred pain from the lower back and doesn’t even result from nerve-root compression. How one person reacts to load, movement, or even stretch, can be very different across the spectrum of people, and it is likely that some people have nerve roots that are just a little quicker to react.

Those with Fibromyalgia suffer from abnormalities in the way that the brain deals with pain. Supra-spinal processes have a top-down enhancing effect on nociceptive processing in the brain and spinal cord. Studies have begun to suggest that such influences occur in conditions such as Fibromyalgia. This means that those who do have Fibromyalgia and sciatica may be far more sensitive to noxious stimuli compared to the general population. Factoring in changes to tissues, stress, load, and movement, those with Fibromyalgia may be more prone to react to these changes by way of producing pain.

Now, very rarely is sciatica mechanical in nature, even issues like nerve impingement are fairly difficult to occur, due to the abundance of room at the nerve root. There are also many cases of actual impingement, where an individual will have no pain. One such study looked at the prevalence of so-called mechanical factors in back pain and found that the majority of people will likely have one or more of these and never know.

Scoliosis

Back pain can be caused by various factors, one of which could be scoliosis, especially if you’re hypermobile. Scoliosis is a condition where the spine develops an abnormal sideways curvature, often starting in childhood but it can occur at any age. It can progress to a severe deformity or remain subtle and stable. However, it is not entirely clear that scoliosis causes back pain as once thought. Despite being a prevalent condition, the reasons why our spine develops this lateral warping remain a mystery.

In some cases, scoliosis has a clear trigger, such as spinal injury or serious disease. In other cases, it appears out of nowhere and continues to develop over time. Although scoliosis seems to increase stress on spinal tissues, it does not necessarily cause back pain. In fact, the link between scoliosis and back pain is still unclear, and the percentage of scoliotic patients with back pain varies from study to study.

While it may seem logical that scoliosis would cause back pain, it is not necessarily the case. Studies have found that scoliosis patients with back pain often share similar characteristics as those with other types of back pain, such as depression and insomnia. Additionally, it is common for healthcare professionals to over-diagnose the impact of scoliosis on back pain, leading to unnecessary treatments and therapy.

Despite the popularity of treating scoliosis with therapy, there is no scientific evidence that suggests therapy can cure or significantly improve the condition. Studies that have been conducted on therapy for scoliosis produce discouraging results, and in many cases, no real conclusions can be drawn. Therefore, it is essential to understand that scoliosis is not the only factor in back pain, and it should not be overly blamed or over-treated.

To further emphasise the non-correlation between scoliosis and pain, Lamar Gant, an American powerlifter, held the world deadlift record for several years despite having been diagnosed with idiopathic scoliosis and displayed a prominent curvature of his spine.

I have put scoliosis into our list of potential specific – back pain causes, however, I do wonder as this area really needs more research. Currently, pain in scoliosis patients is not hugely correlated with the curve size, however, there is evidence that lumbar/thoracolumbar curves are more likely to produce pain in the lower back than thoracic or double major curves, along with the type of asymmetries.

We actually have a great video of r scoliosis, so please feel free to check it out below:

Auto-immune Conditions

One area where medicine has excelled itself in recent years is in the diagnosis and treatment of auto-immune conditions that affect the spine and joints.

This may come as no surprise due to medicine’s never-ending search for a cause-and-effect relationship to things. In the case of auto-immune conditions, the cause-effect relationship is very clear, quantifiable, and often treatable with the correct drugs.

One such example of this is Ankylosing Spondylitis, (AS) a condition whereby the spine becomes fused over time due to inflammation and subsequent deposits on the vertebrae.

AS can be diagnosed through the presence of a gene, HLA-B27, found during blood testing and also has a family link. With such quantifiable factors, doctors are able to recognise the warning signs and take action. Unlike non-specific back pain, where few/no objective findings come from imaging and testing, AS has several hallmark signs which appear through the use of diagnostic imaging such as X-Ray.

Once diagnosed, the treatment for AS varies depending on the severity and reaction to the treatment offered. One area which seems to have had success is the use of Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDS). These drugs alter the inflammation process in the body which in turn slows down the progression of AS.

With such objective findings available, doctors seem to excel in the diagnosis and treatment of auto-immune conditions which affect the back, but continue to flounder when no such findings are available, as seen in the majority of cases related to low back pain.

Does Fibromyalgia Cause Back Pain?

The narrative we hold on Fibromyalgia is this; it is a culturally adopted label to describe a group of symptoms presenting together (the very definition of a syndrome), therefore, it is unlikely that Fibromyalgia causes anything as it is just a word.

However, will people diagnose with Fibromyalgia experience a higher prevalence of back pain? Absolutely, but not likely through a direct cause-and-effect way.

For those in pain, it can cause many other issues that almost act as a feedback loop to make the pain worse. One such example is sleep. The relationship between sleep disturbances and pain has been widely studied, largely showing us that with sleep disturbances comes an increase in pain. It is not only well established that poor sleep directly causes more pain, but, also a sharp decline in physical functioning and mood, especially during the early parts of the next day.

Similarly, studies show that a good night’s sleep only appears to offer a temporary respite to pain, nudging us further down the rabbit hole that pain is an incredibly complex beast, and often at times, just plain weird.

Interestingly, and contrary to popular belief, you cannot bank sleep. Chronic sleep deprivation or a few bad nights can’t be remedied by one long sleep at the weekend. At least that is what the evidence suggests. Several large prospective studies go as far as to suggest that prolonged sleep problems may even increase the risk of developing chronic pain in the future for healthy individuals

So, given that most with Fibromyalgia struggle to get a good night’s sleep, it potentially has the ability to make us more susceptible to developing back pain and general chronic pain. Those with Fibromyalgia are a lot more sensitive to noxious and potential noxious stimuli due to the brain’s top-down enhancing effect on pain processing. Studies have shown that increased activity in the insula cortex of the brain, which is responsible for body perception and emotional processing, can predict the extent and intensity of a patient’s chronic pain.

This means if those with Fibro are more sensitive to stimuli, their brains may take more of an issue with lesser amounts of load, prolonged positional stress, etc, over other people.

These changes to how our brains process information in Fibro are not just seen with lower back pain, they are also pretty prevalent when it comes to issues like fibromyalgia and osteoarthritis.

So, in short, are those with Fibromyalgia more likely to have back pain? Yes, most likely through some of the reasons mentioned above.

When to Worry About Back Pain With Fibromyalgia

It is important to keep in mind that those with Fibromyalgia may attribute new aches and pains, especially back pain, to Fibromyalgia, but this can be dangerous and presents a slippery slope to the top-down processing discussed earlier. Now I don’t write this to scare or inflame, but more so to offer some insight into the issue. So many people with Fibro put off going to the doctors with new pain because they think it is just another Fibro problem, I would urge due diligence if there are certain red flags or if something just does not feel right, definitely do not put off a visit to the doctors or write concerns off as a symptom of Fibromyalgia.

While some early-stage cancers, such as bone cancer in the vertebrae, can be challenging to differentiate from typical back pain, it is uncommon for doctors to conduct cancer tests on every patient with low back pain (less than 2%). However, most cancers and serious conditions will eventually lead to other unique symptoms, which will alert individuals that there may be more going on than general back pain. In rare cases, back pain can be ominous without other symptoms, but typically, persistent low back pain is severe and not life-threatening. It is important not to become overly alarmed, but rather to be aware of the red flags and seek medical evaluation when they occur in combination with persistent and severe pain.

Red Flags For Back Pain Include:

- Neurological symptoms such as weakness, numbness, feeling clumsy and tingling in the back, neck, legs, arms, feet, or hands, which may indicate nerve root compression or spinal cord compression.

- Loss of control over bladder and bowel function, which may be a symptom of Cauda Equina Syndrome (A severe compression of the nerves exiting the spine.)

- Bilateral leg pain

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fever, chills, and a headache that accompanies the back pain, as this could suggest the possibility of a spinal epidural abscess (spinal infection).

- Dizziness, nausea, and/or vomiting

- A new, visible deformity of the spine.

The Usual Treatments for Back Pain

In this section, let’s take a look at some of the usual treatments offered to those with Fibromyalgia and back pain. As you will come to find, when it comes to back pain, Fibro, and research, there is often a big fat “It depends” in the way of a treatment’s effectiveness: mainly as more research is desperately needed.

Yoga For Lower Back Pain

A 2011 study compared the effectiveness of yoga to usual care for individuals with chronic or recurrent lower back pain. The results showed that taking part in a 12-week Yoga program improved back function and reduced disability scores, compared to the usual care group. Although the Yoga group reported higher pain self-efficacy at 3 and 6 months, there was no significant difference in overall pain levels or general health between the two groups. It is important to note that 12 out of 156 people in the Yoga group reported increased pain. In conclusion, Yoga may be a helpful option for those with chronic lower back pain to improve their back function and manage symptoms.

Likewise, Yoga, in some studies, has been found to be just as effective as physical therapy for treating chronic lower back pain in people from underserved communities. In a study conducted with 320 adults with moderate to severe chronic low back pain, participants were divided into three groups: one group received Yoga classes, another group received physical therapy visits, and the third group received educational material about self-care. Results showed that all groups improved in physical function and pain reduction, but those in the Yoga and physical therapy groups were more likely to stop taking pain medication after one year. These findings suggest that a structured Yoga program can be a viable alternative to physical therapy for people with chronic lower back pain.

A bit more Fibro related now and a Cochrane review of 61 trials involving 4,234 mainly females with Fibromyalgia, concluded that the effectiveness of biofeedback, mindfulness, movement therapies (e.g., Yoga), and relaxation techniques remained unclear as the quality of evidence was just to low. So, it’s a bit of mixed bag when the science is reviewed. However, the main point seems to be Yoga is very unlikely to have serious adverse effects and it could potentially help somewhat, but it is on par with just about any other exercise or physical therapy.

Pilates

The effectiveness of Pilates for lower back pain is fairly similar to Yoga, and the research on it is incredibly mixed. Some high-quality randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that Pilates can be more effective than basically doing nothing, in reducing pain in the short term, and that this improvement could be clinically significant.

On the other hand, other RCTs have indicated that Pilates is not superior to any other form of exercise. The results of these studies may be influenced by factors such as the length of the Pilates routine, the type of exercise, and psychological factors. One RCT showed that equipment-based Pilates may have better results in terms of disability improvement and easing fear of movement when compared to mat-based Pilates. However, more research is definitely needed, and it seems that Pilates can provide some benefits for those with Fibro and lower back pain, but it’s likely going to vary from person to person based on variables like context and top-down processing. Likewise, it also looks like Pilates yields better results than hands-on, manual therapy treatment: but active therapy almost always yields better results than passive therapy in the study of pain.

More recently, a large research paper reviewed different types of exercise for treating chronic low back pain. Scientists analysed 118 studies with over 9,000 participants and found pretty much all types of physical exercise helped improve pain and disability, except for stretching exercises and the McKenzie method. The most effective exercises were Pilates, mind-body, strength, and core-based exercises. Pilates was found to be the most effective exercise for reducing pain and disability. The study suggests that people with chronic low back pain should consider doing Pilates or strength exercises as part of their exercise routine. But, as is often an issue with exercise research, the fact that studies are different from each other and that there aren’t many studies that are very reliable are both problems.

Massage

Massage for lower back pain has been a topic of scientific research for several years, with some studies suggesting its potential benefits. However, a review found that there is very little confidence in massage as an effective treatment for lower back pain. The authors had previously declared massage as incredibly beneficial, but their conclusion changed as more data was collected: as is often the case in research. Despite some positive findings, the evidence of massage’s effectiveness is fairly limited and the results of the studies were not consistent enough to draw definitive conclusions. According to the review, there is a need for further research to determine the effectiveness of massage for lower back pain.

Additionally, back pain treatments in general have a long history of being disappointing, with most treatments having little effect beyond that of a placebo. Massage for back pain may still be a worthwhile treatment for some patients, given the help it gives to mental health and stress, but the inconclusive results of the review are somewhat discouraging. As always though, some people swear by massage for pain relief, but when examined a little closer, the benefits could easily be attributed to the tactile and comforting nature of touch and the effect it has on turning down our sensitive nervous system.

Acupuncture

Acupuncture, a traditional Chinese healing method that involves inserting needles into the skin at specific points, has been used by people with Fibro and back pain for a very long time. Likewise, for almost the same duration it has been the subject of much controversy. Some medical journals have published studies which show acupuncture is not effective in reducing pain or treating any other medical conditions. The British Medical Journal published a study in early 2009 that had some pretty discouraging results. Another leading journal in the field of pain and injury, published a harsh scientific evaluation of acupuncture in early 2011, concluding that there was little convincing evidence that it was effective in reducing pain. In 2016, the UK’s NICE guidelines for back pain recommended “not to offer” acupuncture as a treatment option. However, more recently, it has been promoted for use by those with Fibromyalgia and chronic pain.

Despite the lack of evidence supporting acupuncture, many proponents of the practice continue to promote it. Some have even tried to spin negative results as positive. For instance, in a 2010 paper, the authors acknowledged that sham acupuncture was just as effective as real acupuncture, but they still endorsed it.

Another study was conducted to test the effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic shoulder pain in 424 patients. The patients were divided into three groups, with one group receiving Chinese acupuncture in the shoulder, another group receiving sham acupuncture in the leg, and a third group receiving conventional orthopaedic treatment. Although the results of the study appeared promising, the use of sham acupuncture in the leg as a control group was a fatal flaw. In a study on shoulder pain, the sham acupuncture should have been convincing and applied to a location relevant to the shoulder, not the leg. Consequently, patients in the study may have experienced a placebo effect from the “real” treatment, but none from the sham.

This study exemplifies the common shortcomings in acupuncture research, even when it appears satisfactory on paper. The flaws in acupuncture research are often predictable and somewhat amusing, as there are numerous other examples.

Nevertheless, it remains true that acupuncture can alleviate pain for many individuals. This is likely due to the application of noxious stimuli to people in pain, causing modulation of the nervous system, rather than any supposed energy mechanisms. Acupuncture is relatively inexpensive, safe, and effective for some people. The only downside is that it is a passive therapy can promote dependence, and my own bias bites me on the behind here, as I prefer people to feel in control of their own health, rather than relying on someone else or a specific method.

Chiropractic

Chiropractic is a field of medicine that focuses on the spine and nervous system. We are lucky enough at The Fibro Guy to have a qualified Chiropractor as part of the team to offer insights on the use of Chiropractic for chronic pain patients.

The central concept Chiropractic is based on is termed “subluxation,” which refers to a misalignment of spinal joints, believed to cause pain and poor health. However, the scientific community is divided on whether subluxations exist and, if they do, what they actually are. Many doctors and scientists are sceptical of the concept of subluxation and doubt its therapeutic value or application.

Chiropractors have built their beliefs and treatment around the concept of subluxation. However, this definition has been expanded to include any harmful distortion in the body, which many doctors and scientists disagree with. In standard medical terminology, subluxation refers to a partial dislocation of a joint. In contrast, Chiropractors believe that subluxation is the main cause of both back and neck pain and poor health in general. Whilst subluxations are possible in those with high-level connective tissue disorders like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, they have never actually been proven to exist in the general population.

The Chiro field is somewhat split these days, with many clinging to the old beliefs, and others adopting a more Biopsychosocial approach to their treatment, evolving, and adapting as new evidence emerges. This is a good thing, as holding on to outdated theories does not promote growth and can pose a health risk to the public with outdated theories.

Research has shown that pain can distort a person’s mental image of their own anatomy, when combined with negative beliefs around spinal weakness or misplaced vertebrae, many people may well feel they are misaligned and vulnerable, despite it not being the case. A quick adjustment and for some people relief is gained.

In a nutshell, most of the research, including a pretty credible Cochrane review, all say the same thing: spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) is no more effective than inactive treatments, simulated SMT, or other recommended therapies for people with acute low back pain. The scientific evidence for SMT is not very good, plus with the sheer volume of different techniques, it can be hard to determine what actually works and what does not. The conclusion here is; the evidence for SMT is inconclusive, and more research is needed to determine its efficacy, which you were probably expecting.

Just like most things, some people find relief in Chiropractic, however, it is likely not through the proposed methods. It is perhaps a fair assumption then to think of an adjustment as providing a little sensory information through the release of gas and movement through joints, pushing joints into new positions, endorphin release (the happy chemicals) and likely hundreds of other variables involved in the brains processing of sensory input.

Exercise

In the past, it was widely believed that rest and inactivity were the best options for non-specific lower back pain, but recent research shows that exercise can have specific benefits in reducing pain severity, as well as improving overall physical and mental health and physical functioning.

Now, please do keep in mind that exercise and chronic pain is my area, which means that I am going to have some inherent bias toward this section, but I will try my best to keep it at bay!

A fairly recent review that examined 89 studies with 5,578 patients, found that Pilates, resistance training, stabilisation/motor control, and aerobic exercise training were the most effective treatments for reducing pain, and improving physical function, and mental health. However, as I have mentioned before, the quality of the evidence in these studies is often low, and this study is not without its own issues. Overall, though, the study suggests that exercise training is an effective treatment option for adults with non-specific lower back pain, and different types of exercise training can be tailored to individual needs and preferences.

Core stability, according to a study which examined a large amount of data, was found to be more effective than general exercises for short-term relief of chronic back pain. Another study found that success in treating lower back pain with core exercises was not related to improved abdominal muscle function, further helping us to debunk the core myth.

There are many reasons why people may see short terms gains with core stability work though, most likely coming down to beliefs and expectations: people working on what they feel is the problem. Whilst this is good news, other studies do show that these effects only really apply to short-term benefits and are not more effective in the long run.

Managing Lower Back Pain Guidelines

Due to the evidence available around lower back pain, the NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) Guidelines for managing lower back pain and sciatica provide a set of recommendations for healthcare professionals on how to diagnose and treat this condition. As you will see, these are based upon a lot of what we have covered in sections previous.

The first step in the assessment process for your healthcare provider is to consider alternative diagnoses, such as cancer, infection, or inflammation, and exclude these causes through a red flag screening process. Healthcare professionals should also use risk assessment and stratification tools to determine the best course of treatment for each individual. These include:

Imaging is not routinely recommended, except in specialist settings where it may change the course of treatment. The guidelines also emphasize the importance of self-management and exercise for people with low back pain and sciatica., along with validated screening methods like The Keele STarT Back Tool and the Bournemouth Questionnaire.

For non-invasive treatments, manual therapy and psychological therapy may be considered as part of a treatment package including exercise. However, the guidelines do not recommend the use of acupuncture, electrotherapies, orthotics, or traction for managing low back pain and sciatica, which makes sense when we consider some of the evidence reviewed earlier in this article.

Pharmacological management of sciatica and low back pain is also addressed in these guidelines. The use of opioids, gabapentinoids, and benzodiazepines is not recommended for managing sciatica, while NSAIDs may be considered for managing low back pain.

Invasive treatments such as spinal injections, epidurals, and spinal decompression are also discussed, with specific recommendations on when they should be considered. Spinal fusion and disc replacement are not recommended for people with low back pain.

The Takeaway From The Evidence On Treatments

Just like I said at the beginning of this article, research around back pain is just plain messy. There are numerous problems with the research and more studies are desperately needed to increase the quality of evidence available.

It is a fair assumption that the majority of treatments offered to those with Fibromyalgia and back pain do not have quality evidence to back up a lot of claims that are made about them.

With pain comes complexity, this is mainly because people are complicated. Pain does not have a one size fits all approach, there are too many factors which influence the pain experience. Chronic back pain is a debilitating condition that affects millions of people worldwide.

The traditional approach to treating pain by looking for a single tissue or mechanical source does not seem to be the answer, based on an increase year on year in low back pain. Injections, exercise, Yoga, surgery, and even nerve burning have all been used to treat back pain, but these treatments do not always provide long-lasting relief, and in some cases none at all. Scan results also do not always relate closely to pain levels, as some people may have “abnormal” findings without any pain, while others may have normal-looking scans and experience significant pain.

Treating chronic pain should involve a more holistic approach that truly encompasses all of the factors which make us human: such as factors that may contribute to chronic pain.

The Fibro Guy practitioners do not really like word exercise, it comes with certain negative preconceptions for people in pain, we much prefer the word movement. Movement is far less scary and really denotes it is a normal part of a functioning body and brain. This is why we use it as an inroad to helping people dispel negative associations and connections to pain, as well as the many secondary benefits that come with movement.

Fibromyalgia Back Pain Exercises

Now that we’ve discussed the value of movement and how it can help alleviate chronic back pain associated with fibromyalgia, we’d like to share a practical resource with you. We’ve created a video that walks you through a series of back pain rehab exercises specifically designed for those living with fibromyalgia.

These exercises are not about rigorous training or pushing your body beyond its limits. Instead, they’re about gently engaging your muscles and joints, promoting flexibility, and encouraging a healthier relationship with movement.

The routine in the video incorporates a blend of stretching, strengthening, and mindfulness techniques, all aimed at reducing back pain and enhancing your overall well-being. The exercises can be easily followed and done from the comfort of your home, making it a versatile tool in your fibromyalgia management toolkit.

As you start to incorporate these exercises into your routine, remember, it’s not about perfection. It’s about listening to your body, moving at your own pace, and noticing how your body responds. If you feel any discomfort during the exercises, pause, take a break, or modify the movement to better suit your body’s needs.

Adam

———

The Fibro Guy™

Enjoyed Our Blog? Why Stop Here?

Reference:

Blanchette, M., Stochkendahl, M., Borges Da Silva, R., Boruff, J., Harrison, P. and Bussières, A. (2016) ‘Effectiveness and Economic Evaluation of Chiropractic Care for the Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review of Pragmatic Studies’, PLOS ONE, 11(8), e0160037.

Brinjikji, W., Luetmer, P.H., Comstock, B., Bresnahan, B.W., Chen, L.E., Deyo, R.A., Halabi, S., Turner, J.A., Avins, A.L., James, K., Wald, J.T., Kallmes, D.F. and Jarvik, J.G. (2015) ‘Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations’, American Journal of Neuroradiology, 36(4), pp. 811-816.

Choy, E.H.S. (2020) ‘Sleep Dysfunction in Fibromyalgia and Therapeutic Approach Options’, OBM Neurobiology, 4(1), 049.

Furlan, A.D., Giraldo, M., Baskwill, A., Irvin, E. and Imamura, M. (2015) ‘Massage for low-back pain’, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9), CD001929.

Holtzman, S. and Beggs, R.T. (2013) ‘Yoga for chronic low back pain: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials’, Pain Research & Management, 18(5), pp. 267-272.

Licciardone, J.C., Pandya, V., and Gudavalli, R. (2025) ‘Longitudinal outcomes among patients with fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain, or localized chronic low back pain’, The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, ahead of print.

Manchikanti, L., Knezevic, N.N., Navani, A., Christo, P.J., Limerick, G., Calodney, A.K., Grider, J., Harned, M.E., Cintron, L., Gharibo, C.G., Shah, S., Nampiaparampil, D.E., Candido, K.D. and Soin, A. (2022) ‘The Specifics of Non-specific Low Back Pain’, Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, 12(4), e131499.

Martín-Martínez, J.P., Villafaina, S., Collado-Mateo, D., Pérez-Gómez, J. and Gusi, N. (2021) ‘An Observational Study Comparing Fibromyalgia and Chronic Low Back Pain in Pain Impact, Somatosensory Function, Motor Functionality, and Balance’, Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(23), 5629.

Puntumetakul, R., Yodchaisarn, W., Emasithi, A., Keawduangdee, P., Chatchawan, U. and Yamauchi, J. (2021) ‘Effects of Core Stabilization Exercise versus General Trunk-Strengthening Exercise on Balance Performance, Pain Intensity and Trunk Muscle Activity Patterns in Clinical Lumbar Instability Patients: A Single Blind Randomized Trial’, Walailak Journal of Science and Technology, 18(7), 9054.

Rubinstein, S.M., de Zoete, A., van Middelkoop, M., Assendelft, W.J.J., de Boer, M.R. and van Tulder, M.W. (2019) ‘Benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy for the treatment of chronic low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials’, BMJ, 364, l689.

Vickers, A.J., Cronin, A.M., Maschino, A.C., Lewith, G., MacPherson, H., Foster, N.E., Sherman, K.J., Witt, C.M., Linde, K. and Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration (2012) ‘Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis’, Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(19), pp. 1444-1453.

Vickers, A.J., Vertosick, E.A., Lewith, G., MacPherson, H., Foster, N.E., Sherman, K.J., Irnich, D., Witt, C.M., Linde, K. and Acupuncture Trialists’ Collaboration (2018) ‘Acupuncture for Chronic Pain: Update of an Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis’, The Journal of Pain, 19(5), pp. 455-474.

Wolfe, F., Clauw, D.J., Fitzcharles, M.A., Goldenberg, D.L., Katz, R.S., Mease, P., Russell, A.S., Russell, I.J., Winfield, J.B. and Yunus, M.B. (2010) ‘The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity’, Arthritis Care & Research, 62(5), pp. 600-610.

Wolfe, F., Clauw, D.J., Fitzcharles, M.A., Goldenberg, D.L., Häuser, W., Katz, R.L., Mease, P.J., Russell, A.S., Russell, I.J. and Walitt, B. (2016) ‘2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria’, Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 46(3), pp. 319-329.

Wu, A., March, L., Zheng, X., Huang, J., Wang, X., Zhao, J., Blyth, F.M., Smith, E., Buchbinder, R. and Hoy, D. (2023) ‘Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021’, The Lancet Rheumatology, 5(6), e316-e330.

Yağcı, İ., Akcan, E., Yıldırım, P., Ağırman, M. and Güven, Z. (2010) ‘Fibromyalgia Syndrome in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain’, Archives of Rheumatology, 25, pp. 37-40.