- Breakthrough For Ehlers Danlos Syndrome and Endometriosis - 13 March 2025

- Does EDS get worse as you age? - 20 February 2025

- Can Ehlers Danlos Syndrome Cause Weight Gain/Loss? - 18 February 2025

Please click below if you prefer to listen to this article on Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

I first wrote this article on Parsonage-Turner syndrome way back in 2017, and in the years since, I have worked with more people with PTS. So, I wanted to revisit this article to add more information for people regarding exercise and rehab for those living with PTS.

This article covers:

ToggleWhat is Parsonage-Turner syndrome?

Parsonage-Turner syndrome (PTS), also known as Neuralgic Amyotrophy, is an uncommon neurological disorder characterised by a rapid onset of severe pain in the shoulder and arm. This acute phase may last a few hours to a few weeks and is followed by wasting and weakness of the muscles (amyotrophy) in their affected areas. For those with PTS, daily tasks that most of us take for granted can become increasingly difficult over time, as weakness, atrophy, and pain interfere with everyday tasks.

Parsonage-Turner syndrome mainly involves the brachial plexus, the network of nerves that extend from the spine through the neck, into each armpit, and down the arms. These nerves control movements and sensations in the shoulders, arms, elbows, hands, and wrists. However, other nerves in the arm or leg can also be involved.

What causes PTS?

Whilst not much is known about the causes of Parsonage-Turner syndrome, researchers suspect that most cases are due to an autoimmune response following exposure to an illness or environmental factor.

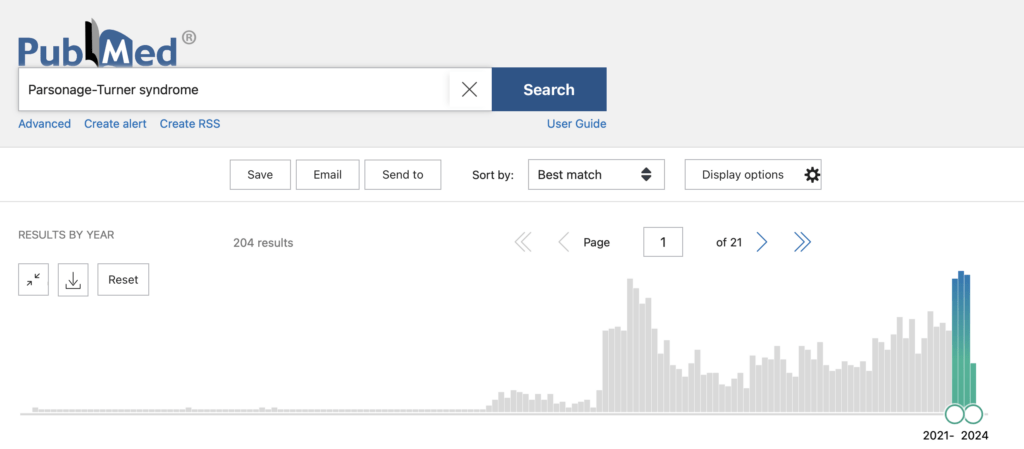

Now, back in 2017, when I first met Alison (you will meet her soon), I was astounded by the sheer lack of research on PTS, with Pubmed yielding around 1,700 articles on the topic (and 1,783 for Neuralgic amyotrophy). Sadly, in 2024, when I looked again, that number has only risen to 1,996 (and 2,096 for Neuralgic amyotrophy)

However, as you will see from the image below, there has been a recent uptick in research into PTS. Now, I wonder why this might be.

If only something were health-destroying around 2019: oh, Covid-19!

As it turns out, there are a fair amount of folks who developed PTS after vaccinations (which we did know about already. The issue is that with the COVID-19 pandemic, more people than at any other time in history were getting vaccinated.

This study investigated the association between Parsonage-Turner Syndrome and both COVID-19 infection and vaccination. A systematic literature review, including 44 case reports and 10 case series comprising 68 patients (so not a super strong review), found that middle-aged males were predominantly affected. The study reveals that PTS symptoms appeared, on average, 11.7 days after vaccination and 20.3 days following COVID-19 infection. The Pfizer vaccine was most frequently linked to post-vaccination cases, accounting for 53%. The axillary, suprascapular, and musculocutaneous nerves were commonly involved in both groups. Notably, partial symptom improvement was observed in 78.1% of post-vaccination cases, compared to 38.9% of post-infection cases. The findings suggest that PTS manifests more quickly after vaccination than after infection, with most patients experiencing some degree of recovery.

What was found in the previous study seems to be across the board. A far better (and far more recent) systematic review of 59 cases from two databases found PTS was agian more common in males, with sudden pain typically occurring within two weeks post-vaccination. Most cases involved unilateral PTS, with common symptoms including pain, motor deficits, amyotrophy, paresthesia, and sensory loss. Differences were noted between mRNA and viral vector vaccine groups. Some cases showed nerve involvement beyond the brachial plexus. Notably, PTS could recur with subsequent vaccinations. This evidence indicates PTS can follow any COVID-19 vaccine type, with varying subgroup characteristics.

Conversely, back in 2017, COVID hadn’t hit yet, so the studies available have not mentioned it. In the very limited studies conducted with those living with Parsonage-Turner syndrome, for many, there were no triggering events or any underlying cause that could actually be identified. However, certain factors known to trigger some cases include:[1][2]

• Infections (both viral and bacterial)

• Surgery

• Vaccinations

• Childbirth

• Spinal taps or imaging studies using radiologic dye

• Strenuous exercise

• Certain medical conditions, including autoimmune disorders

• Injury

Recent improvements for those with PTS

It saddens me that it took a global pandemic to push researchers to look into PTS more, and even then, they didn’t do anything to really push things forward with PTS. However, with that being said, covid did do us a favour in regards to a couple of things:

Improved imaging methods in MRI and high-resolution ultrasound have identified structural peripheral nerve pathologies in PTS, most notably hourglass-like constrictions, which has positively affected getting diagnosed properly.

The shift towards recognising the inflammatory nature of neuralgic amyotrophy. Consequently, finding that early intervention with high-dose steroids during the acute phase can mitigate severe pain and inflammation, potentially improving long-term outcomes.

However, despite this, we still have a massive lack of research into PT. Whilst the exact cause and mechanism of Parsonage-Turner syndrome are not well known, we do know that the effects can be incredibly debilitating and cause much distress. The severity of the disorder can vary widely from one individual to another due in part to the specific nerves involved. Affected individuals may recover without treatment, meaning strength returns to the affected muscles and pain disappears. However, individuals may experience recurrent episodes. Some affected individuals may experience residual pain and potentially significant disability.

Alison: The first person I ever met with PTS

When my client Alison first came through the studio doors in 2017, I first heard the words Parsonage-Turner syndrome. Considering we both had no idea what to expect, she did incredibly well on the programme, and the whole experience was a fantastic learning curve for both of us.

When Alison stepped into the studio, she had one goal in mind: to regain some function in her upper body and be able to breathe properly again. Here at “The Fibro Guy,” our expertise is around conditions such as fibromyalgia and Hypermobility; however, I did notice a lot of commonalities between PTS and how we work with those with Hypermobility syndromes in the studio (as they are more from a neurological approach as well).

So, I set out to learn as much as possible about Parsonage-Turner. I slowly tweaked our hypermobility framework to help Alison better connect to her tissues and help her motor system move and control them again. Then, we started on the mammoth task of restoring her functions.

The following is from Alsion about living with Parsonage-Turner syndrome, and for many of you, I imagine it rings true:

“My world was turned upside down last November when I felt the start of the symptoms that were to rule my life for the next six months. I was travelling to my son’s house when I noticed that the steering felt heavy on the right side. So I pulled over and checked the tyre pressures. They felt fine, so I dropped the car off at the local garage. The next day, the garage confirmed that there were no issues with the car and that the steering wasn’t as heavy as I had described.

A few days later, I noticed that my lungs felt like they had popped when I tried to walk to the car park after work. I could see the car but couldn’t reach it, as I couldn’t breathe. My GP prescribed antibiotics and said it was a chest infection and possibly a trapped nerve in my shoulder and recommended that I come back on Monday if I felt no better. He sent me for an X-ray when I returned to see a different doctor. The next day, the new doctors phoned with the results, saying, “I’m sorry, but I’ve never seen anything like this before; I don’t know what to do and will have to ring the hospital consultants as your liver is halfway up your chest on the right side.

I was in utter disbelief, and I remember thinking, how was this possible?

Throughout the next couple of months, my pain levels in my arms and shoulders reached about 9 out of 10 every day, and I couldn’t lie flat to sleep. My mouth felt like I had the worst toothache ever, and I suffered gastric reflux with a very dry mouth and total exhaustion. The use of my arm was getting more limited every day, and by Christmas, I couldn’t use a knife and fork as the nerves in my hands were losing their ability to send the signals to enable me to move.

I was told that I had to have a CT scan, but I couldn’t lie flat. They managed to prop me up a bit, and I managed. This showed that my diaphragm was raised on the right side, squashing my lung into a tiny space. There was a shadow on my other lung, and my liver had a cyst on it; just in case that wasn’t enough, I have a 3cm nodule on my thyroid. OK, so what are you going to do about it? Nothing till you see the consultant was the response.

I was soon referred to a gastro-intestinal specialist who told me they deal with below the diaphragm, and my biggest problem was above. I was told that I would have to wait to see a Respiratory consultant, but he would ring Freeman Hospital to see if they knew what was going on with me. “She has a bilateral paralyzed diaphragm”, was the response. I was told that it could be Neuralgic Amyotrophy. I soon began searching the internet and read many sorties from people living with Parsonage-Turner syndrome.

Neuralgic Amyotrophy can be caused by vaccinations, injury, or, as probably the case for me – exposure to a virus. It is a rare autoimmune condition where the body attacks itself. Doctors knew nothing about it – hardly surprising as different names, such as Brachial Neuralgia, Neuralgic Amyotrophy, or Parsonage-Turner Syndrome know it. I’ve never met anyone else with it, but due to finding a support group on Facebook, I now know more about it than my doctors do. It is a nightmare when different parts of your body are affected as our NHS carves you up into different bits, and doctors only know their little bit. So far, I have seen gastro-intestinal patients who then called the Cardio Thoracic, Respiratory, Endocrine, Neurology and Oral. They insist it is a one-off event, yet some people have repeat episodes. I’m hoping I’m not one of them!

A friend with Fibromyalgia told me about Adam at “The Fibro Guy” who works with those with chronic conditions and who had personally helped her to transform her life, and if nothing else, I should at least speak to them. When I discovered that my local studio was only five minutes from my home, it seemed like it was meant to be, so I emailed Adam with some details of my problems.

Poor Adam didn’t know what to expect when I started, as sometimes the nerves don’t succeed in sending messages to my muscles, but I sat down with him, and we worked together to formulate a blueprint for me to regain my function.

Our journey together was a huge learning curve, not only for me but for Adam as well. However, he kept tweaking my programme until we found what worked for me. He is patient and funny, and I enjoy every minute of our sessions. Considering I was nervous about rehab in the first place, it has been really enjoyable progress, and I already feel so much better. I am struggling to lose weight as I am now trying to rebuild my muscles that are atrophied due to the condition. I am losing inches, though, and my pain is now 1 most days, with the odd one that reaches maybe 5.

That is in comparison to constant 9. Mentally, I am much more positive about returning to normal and have started fishing again. I am a fly-fishing coach, mainly trying to get more women and juniors into the sport. It is fantastic for anyone who is going through a bad time. You have to think about how to target the fish—where are they swimming, deep or near the surface, and what are they eating? This stops you from thinking about your pain, your woes and what you can’t do! More importantly, it was a huge part of my life, and I didn’t think I would ever be able to do it again. I can now. I’m getting my life back slowly, thanks to Adam and my strong will!

Exercise and Rehab for Parsonage-Turner syndrome

Over the years, I have worked with a few others with PTS, which is mainly down to them reading this blog! So, I want to quickly cover the 3 main tips I feel are important to work on regarding PTS rehab.

Tip 1: Neurology over muscles

What I mean by this is that it makes no sense to start trying to move weights around if you can’t even connect to the muscle you’re trying to move. One of the things that gets affected in PTS is the motor system, so you need to get both the somatosensory maps of the body and the motor maps, singing from the same song sheet.

To elaborate, it’s crucial to help the sensory map accurately represent the body first. The Sensory Map, located in the postcentral gyrus of the parietal lobe, acts as the brain’s sorting centre where sensory input is processed, understood, and sent off to inform our every move, thought, and reaction. Think of it like Google Maps; each part of your body is represented within this sensory map, and it’s dynamic, constantly updating based on sensory experiences, injuries, and learning.

Our sensory map is refined through experience, like colouring in a sketch of a map at birth with life’s experiences detailing the roads and pathways. This detailed representation is crucial because more sensitive areas, like fingers for typing or the tongue for speaking, require finer control and, therefore, command larger areas on the sensory map.

Once the sensory map accurately represents the body, focus shifts to the motor map, located in the precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe. The motor map orchestrates voluntary muscle movements, from threading a needle to sprinting. Like the sensory map, it is organized based on the complexity of movements rather than the size of the body part. Hands and faces, requiring intricate movements, take up more space on this map.

Both maps must sync for graceful movement and accurate, up-to-date information sharing. This interplay ensures smooth, efficient movements. When this communication is disrupted, simple actions can become challenging. Focusing on neurology first ensures that the sensory map accurately represents the body, allowing the motor map to execute precise movements effectively. This holistic approach is essential in managing conditions like PTS, where the motor system is impacted. For more detailed info on cortical maps and motor systems, read our hypermobility and exercise article, which covers in depth.

Tip 2: Use tactile cues

As I mentioned above, the sensory and motor sides of rehab are very important for PTS. Tactile cues can help with this. A tactile cue is any form of sensory input that activates the corresponding representation of the joint in your brain’s sensory map. Using tactile cues, such as bands or hands-on techniques, provides immediate feedback to your sensory map, giving you a better sense of control and engagement and creating a more accurate motor output. This helps integrate sensory and motor maps, which are crucial for effective movement and stability.

For instance, placing a band behind your knee and pulling it forward provides a tactile cue that pulls the joint into flexion. This action triggers proprioceptors that inform your brain about the movement, creating a prediction error. Your brain then adjusts by better locating the joint, connecting to it, and activating more muscle fibres to counter the pull. This results in immediate stability as long as the cue remains, allowing you to integrate motor movements with a better-established sensory map.

Using tactile cues helps your sensory map accurately represent your body. If you use resistance bands as a tactile cue, the extra force will generally result in your brain allowing you to recruit more muscle fibres than it would normally allow. This leads to stronger and more precise motor outputs. This means you can start loading the joints and working through very small ranges of motion, helping to establish and strengthen the sensorimotor link. Doing so builds a foundation for improved movement and stability, which is essential for your recovery from PTS.

As shoulder blades are very much affected in PTS, below is a video on a simple tactile cue exercise for the shoulder blade, taken from our hypermobility exercise library.

Tip 3: Focus on the Shoulder Girdle

In Parsonage-Turner Syndrome (PTS), focusing on the shoulder girdle is essential for a few reasons. One key aspect is increasing muscle tone to help keep the thoracic outlet open and reduce the risk of compression. Additionally, the serratus anterior muscle plays a vital role in breathing by helping lift the ribs. Here’s why these points are important:

Increasing Muscle Tone

Strengthening the muscles around the shoulder girdle is crucial for keeping the thoracic outlet open. The thoracic outlet is a space through which nerves and blood vessels pass from your chest to your arms. When the muscles in the shoulder girdle are weak, this space can become compressed, leading to pain, numbness, and further complications. By increasing muscle tone in this area, you can ensure that the thoracic outlet remains open, reducing the risk of additional compression and associated symptoms.

Importance of the Serratus Anterior

The serratus anterior muscle, located on the side of your rib cage, is particularly important in PTS rehabilitation. This muscle helps lift the ribs during breathing, which is essential for effective respiration. Proper breathing mechanics can improve oxygenation and reduce fatigue, which is particularly important for individuals recovering from PTS. Additionally, the serratus anterior stabilises the scapula (shoulder blade) against the thoracic wall, allowing for better shoulder mechanics and reducing the risk of injury.

I hope you enjoyed the article and a good luck with your own rehab.

-Adam-

FAQs on Parsonage-Turner Syndrome

What is the pain pattern of Parsonage-Turner syndrome?

Parsonage-Turner syndrome typically begins with a sudden, intense pain in the shoulder and upper arm. This acute pain can last from a few hours to several weeks, often followed by muscle weakness and wasting in the affected areas. As the initial severe pain subsides, it may be replaced by a persistent, dull ache and noticeable difficulty in everyday tasks.

Can you fully recover from Parsonage-Turner syndrome?

Recovery from Parsonage-Turner syndrome can vary greatly. While some individuals may experience a complete recovery with no lasting effects, others may continue to struggle with weakness, pain, or disability. Early intervention with targeted rehabilitation exercises can significantly improve outcomes, but unfortunately, some may experience recurrent episodes or have lingering symptoms.

What triggers Parsonage-Turner syndrome?

The exact cause of Parsonage-Turner syndrome remains largely unknown. It’s believed to be triggered by an autoimmune response following factors such as viral or bacterial infections, surgery, vaccinations, childbirth, spinal taps, strenuous exercise, or other medical conditions. In many cases, however, no specific trigger is identified.

Can I exercise with brachial neuritis?

Yes, exercising with brachial neuritis is possible, but it should be done under the guidance of a healthcare professional. The focus should be on gentle movements to maintain range of motion and gradually strengthen the affected muscles without causing further pain or nerve damage.

What are the best exercises for a brachial plexus injury?

For a brachial plexus injury, effective exercises include:

- Range of motion exercises: Gentle stretching to keep the joints flexible.

- Strengthening exercises: Light resistance bands or weights to build muscle strength slowly.

- Neurological exercises: Techniques like tactile cues and proprioceptive training to improve nerve function and sensory-motor integration.

- Shoulder girdle exercises: Strengthening the muscles around the shoulder to support and stabilise the area.

What is the prognosis for Parsonage-Turner syndrome?

The prognosis for Parsonage-Turner syndrome varies widely. Many people see significant improvement within one to two years, but some may have persistent symptoms or recurrent episodes. Early diagnosis and proper treatment, including physical therapy, are crucial for better long-term outcomes.

Can Parsonage-Turner syndrome affect legs?

While Parsonage-Turner syndrome primarily impacts the brachial plexus in the shoulders and arms, it can sometimes affect other nerves, including those in the legs, although this is less common.

How do you recover from Parsonage-Turner syndrome?

Recovery involves a combination of rest, pain management, physical therapy, and sometimes medications like steroids to reduce inflammation. Rehabilitation focuses on restoring muscle strength, improving nerve function, and maintaining range of motion.

Can Parsonage-Turner syndrome be permanent?

In some cases, Parsonage-Turner syndrome can cause lasting damage, resulting in ongoing pain, weakness, or disability. However, many individuals achieve significant recovery with early intervention and proper management, allowing them to lead relatively normal lives.

Is Parsonage-Turner syndrome worse at night?

Pain from Parsonage-Turner syndrome can often be worse at night, likely due to decreased distractions and the body’s natural rhythms, which can make pain sensations more pronounced. Additionally, certain positions while lying down might exacerbate nerve compression, increasing discomfort.

How many people get Parsonage-Turner syndrome a year?

Parsonage-Turner syndrome is relatively rare, with an estimated incidence of 1-3 cases per 100,000 people annually. However, it may be underdiagnosed due to its rarity and variability of symptoms.

Does neuropathy get worse when lying down?

Neuropathy symptoms can worsen when lying down due to changes in blood flow, nerve compression, and the absence of distractions, making pain more noticeable. This can be particularly true for conditions like Parsonage-Turner syndrome, where nerve pain is a significant symptom.